The Daily Worker Newspaper, September 25, 1926, Page 10

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

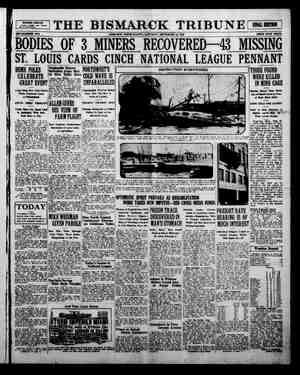

Class War HE celebration of Labor Day, the apotheovis of the respectability of the official labor movement has once again been enacted, with the usual touching scenes of fraternization between capital and labor—- with ammy, church and Wail Street patting labor on the back and praising it for being a faithful and obedi- ent servant and bringing in fat dividends and keeping the Reds in their place. This is a good time to turn back—just by way of contrast—to those stormy days forty years ago when America’s real Labor Day was born in the midst of violent conflict between the class- es. No farce that, but a tremendous drama of class struggle from which the revolutionary workers of every European country have drawn inspiration for the day which has become a sort of rehearsal for revo- lution; a day when capitalist governments are afraid and troops are massed in all the industrial centers. (May 1, 1886, was the culmination of a movement of the greatest significance in the history of the Ameri- can proletariat. It marked its conscious entrance into the arena of class struggle. “I only wish that Marx could have lived to see it,” writes Engels to a friend, a month later. “What the downbreak of Russian czar- ism would be for the great military monarchies of Europe—the snapping of their mainstay—that is for the bourgeoisie of the whole world the breaking out of class war in America . the way in which they (the American proletariat) have made their ap- Pearance,.on. the scene ts quite extraordinary-—six mnths ago nobody suspected anything, and now they appear all of a sudden in such organized masses as to strike terror into the whole capitalist class . . .” Never before or since, in this country, has the irre- concilable antagonism between capital and labor and the inevitability of class war been stated with such openness and realism es it was by both sides in the eighties. With the final swallowing up of the last traces of the public lands by the great corporations, “American labor was” as Commons put it, “now per- manently shut up in the wage system.” And labor conditions at this period were excellently calculated to drive into the minds of the workers a realization of the intolerable slavery which that system involved, and their last illusion of the possibility of escape gone, to goad them into turning at bay. The tremendous displacement of man power by ma- ehinery in the course of the preceding decade and a half had driven hundreds of thousands of skilled work- erse—a large native element among them-—into the ranks of unskilled labor. An official report published in 1886, puts the dis- placement in the silk industry (“in the last few years only”) at 90 per cent in winding and 95 per cent in weaving; in cotton goods, at 50 per cent (“in the last 10 years”); in the manufacture of agricultural ma- ehinery, at 50 per cent; of shoes “in some casés 80 per cent, in others 50 per cent to 60 per cent,” and so on for a number of other industries, The huge immigration of this decade, over 5,000,000, aggravated the situation. The labor market was great- ly. overstocked. Moreover, capitalists had discovered that profits hitherto unheard of could be made from’ the exploitation of children, and in many lines adult labor was being rapidly superseded by child labor. r) ; Troops Firing on Labor Demonstration, Baltimore 8t., Philadelphia. in America in By Amy Schechter. (Decorations by Jerger) In a number of towns, parents were unemployed while their children were working, Then came the great depression of 1884-1885. Wages were slashed again and again. In the mines, where some of the hottest struggles of the pertod were fought, the cut was 40 per cent. The textile workers were also very hard hit. In Paterson, for instance, wages were reduced 50 per cent within three years. Large num- bers of mills were shut down. Contemporary press descriptions of the streanis of. starving textile work- ers wandering about in a despairing search for bread might be taken from an account of the Russian famine. The following is taken from the Hartford Examiner’s account of the textile region along the Willimantic in February, of 1885: oP “Since July, fifteen of these concerns have shut out their employees, and their inability to find work has brought starvation nearly unto death . . ,. Im the severity of the winter young girls have tramped from place to place in search of work, have begged shelter and food and slept in outhouses and barns, and are to- day the victims of hunger and exposure . . . the males tramp out farther in the state and be- come desperate . . while the old people and in- fants remain in the villages starving by imches . . .” Not only were wages extremely low and, in many cases paid monthly, but the pleasant practice of hold- ing back 15 to 20 days’ pay out of a month’s, sometimes till the end of the year, or even of the term of em- ployment, “so that,” writes the Commissioner of La- bor, “the poorest paid and most numerous classes are thus unable to exist from pay-day to pay-day without credit.” The masses of unskilled workers lived in an eternal round of debt. Hours for this class of labor were from eleven to twelve in states where legisla- tion had already been enacted; in other states any- thing up to twenty, and in all states hours were limit- less for tenement industry. Pennsylvania miners worked up to 18 hours. Minnesota passed a law- limit- ing work on the railroads to 18 hours a day. Horrible things were done to the children of the proletariat. Thruout the country children from eight, in the south from six years worked eleven, twelve and thirteen hours a day under unspeakable conditions. Often, as in the Harmony Mills, in Cohoes, N. Y., known to workers as “Hell’s Mills,” children were flogged with leather straps when they could not keep up the pace required. The mill owners said that “They were\kept under control in a way that benefited their morals .. .” A superintendent, either uncommonly naive or uncommonly stupid, told the Labor Bureau officials, “Now, I have noticed a strange thing. Fami- lies come here from Ireland and the girls are as rug- ged and healthy and rosy-cheeked as you would ever see, and yet in two years the girls woul& be consump- tive, and half the family would be gone in seven years.” In New York City we read of children working at strip- ping and preparing tobacco, “11 to 13 hours, not as long hours as grown persons, but enough to kill them rapidly.” Tens of thousands of workers grew up illiter- ate because they had been shut up in the factories since earliest childhood. In mill as well as mining towns workers were com- pelled to live in the filthy tenements provided by the companies at exorbitant rents. The Fall River “Cotton Manufacturer” wrote of these tenements, “They are 10t as good as we would like to have them, but they ive good enough for operatives.” At the beginning of the decade capital believed that under existing circumstances the great mass of un- skilled and defenseless was completely in its power, and open to limitless exploitation. But gaining im- petus during the destitute years of the 1884-1885 de- pression, a great wave of revolt swept thru this class of Jabor, “an elemental protest against oppression and degradation,” manifesting itself in thousands of furi- ouslyfought strikes, and carrying hundreds of thou- sands of workers into the Knights of Labor. In the year from July, 1885 to July, 1886, membership rose from 104,066 to 702,924. “The movement bore in every way the aspect of a social war,” writes Commons. “A frenzied hatred of labor for capital was shown in every important strike . . . Extreme bitterness to- wards capital manifested itself in all the actions of the Knights of Labor, and wherever the leaders undertook to hold it within bounds they were generally . ed by their followers, and others who would lead as di- rected ‘were placed in charge . . .” f This great mass movement of the proletariat—‘“that mighty and glorious movement,” Engels calls it—creat- ed panic in the ranks of capital, with its force and its swiftness, its destruction of the barriers of craft and nationality and race,.its direction toward “the solid- arity of all labor.” for the first time organized revolutionary propaganda was gaining a real foothold in the general labor move- ment. , In the farywest the Red International, preaching a To add to this was the fact that |‘ Police Breaking Up a Labor Meeting in’ West Side Turner Hall, Chicago. somewhat unclear but militant socialism exerted some influence. But the revolutionary party that was be- coming a real force among the workers was the Black International, affiliated with the anarchist Internation: in Europe. In the New York section, led by Johan} Most, simon-pure anarchy prevailed. But in the midd! west and the west, particularly in Chicago, which was the stronghold of the movement, a sort of anarcho-syn- dicalism prevailed. The practical result of their theories meant a close connection with the unions and participation in the daily struggles of the workers. In every big Chicago strike of the period we find»the an- archists—or Communists, as the bourgeois press called them—in the front ranks, leading and organizing. By 1886 the Black International had between six and ten thousand members. Of these at least 2,000 were in Chicago, and included a large English speaking ele- ment. The party exerted a powerful influence over very much larger numbers. In Chicago, for instance, the Central Labor Union, to which the majority of the unions in the city were affiliated, was completely under anarchist control, co-operating with the Inter- national in all iis parades and demonstrations, and spreading revolutionary propaganda among the thou- sands of unemployed, who tramped the streets of the Capital, then, was thoroly afraid, and openly and thru its official spokesmen talked class war and prep- aration for the forcible suppression of the proletariat. Labor replied by announcing that it would meet force with force, and by forming armed defense units in con- nection with unions, anarchist groups, and other work- ers’ organizations. General Sherman, Chief of Staff of the U. 8. Army, in an official speech on Governor’s Island declared: “There will soon come an armed contest between Capital and Labor. They will oppose each other not with words and arguments, and ballots, but with shot and shell, gunpowder and cannon. The better class- es are tired of the insane howlings of the lower strata, and they mean to stop them.” The San Francisco “Truth” influential in the west, answered with the following call: “Working people of America! I tell you these words are not mere mouthings . . they mean blood . .. because you dare to ask for what is your own, the full product of your own labor . . Arm yourself at once the day of battle will be upon us long before we are prepared ,.. This sign, thig speech of Sherman, is deadly in its significance. We have no moment to waste .. .” Commenting on a strike, the Chicago Times remark- ed that “Hand grenades should be thrown among those who are striving to obtain higher wages, since by such treatment they would be-taught a valuable lesson and other strikers would take warning of their fate.” : In a furious reply, the Labor Unionist of Akron, Ohto (neither socialist nor anarchist) cries: “God speed the day that hand grenades will be thrown among honest men, who asking for their just right, when refused, quit work . . . That day would be the dawn of deliverance for enslaved labor . . .” The Unionist then goes on to recommend the institu- tion of a military order by the Knights of Labor, “for, if such teachings as “the above go on, the day is not far distant when the laboring man -will need to know the use of firearms. The organs of monopoly teach giving us hand grenades . , , Let us be prepared when they are ready to open the ball and let them dance to the music of a little dynamite and hot shot If the organs of monopoly wish to hasten. the let them preach the hand grenade Come on, monopoly, with your hand gren- revolution . . . doctrine.” ades! There was continual talk of enlarging the army for ZaPs° BS @zxRA 7 Sme«eee = Peas et b he eeortaasS gi