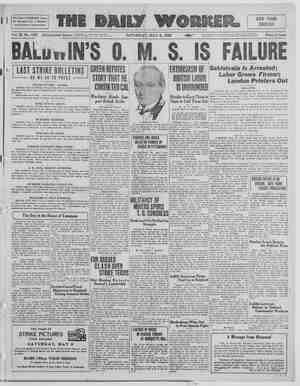

The Daily Worker Newspaper, May 8, 1926, Page 8

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

DISCHARGED P'SCHARGED! He was dazed, stunned. It had come like a bolt. from the blue. He could hardly believe he had heard right. On his poor old face dawned such a look of start- led fear that the foreman was touched to an ex- pression of sympathy. “T’m sorry, Tom.” “But Mr. Brown—” “Tt ain’t me, Tom; it’s the superintendent.” “The superintendent!” “You see, Tom, you're gettin’ too old for this job. Lately you’ve been packin’ thirty and forty pounds of. rosin to the box when you should be totin’ sixty. That slows up produc- tion, Tom; so the superintendent’s been bawl- in’ hell outa me for keepin’ you. He says to let you go and get a younger feller.” The gnarled hands 6f the old worker clutched at the foreman’s arm convulsively. “Don’t do that, Mr. Brown; give me another chance. I can carry the full load. You see if I can’t.” But the foreman shook his head. “No, no, Tom! It would be all right with me; but the superintendent—” “Maybe if I see him. Ps “It won’t do any good, Tom.” But the old worker would not be convinced. He made his trembling way to the factory office of Sherman & Wilson, paint and varnish manu- facturers. The superintendent looked annoy- ed at seeing him. It always made him feel bad, anyway, to have to let an old employe out—es- pecially one who had stood by the firm during the labor trouble fifteen years ago, and who had been on the payroll for nearly twice that length of time; but you can’t afford to run business on sentiment. The varnish room was behind now on orders, and a younger, faster man was absolutely needed. “Really, Tom, we’re doing you a favor. What you want is something not so heavy. That’s the thing to do; get a lighter job.” “But where—how—?” “Oh, you’ll find lots of ’em if you look. Sure you will! No need to worry. Light portering, Tom; that’s the ticket! Send anyone to me for references. And now. now. . The old man found himself outside the office walking blindiy down the passageway. In the locker-room he sat for a long time _ before changing from his paint-stained overalls and jumper into the worn gray suit which was at the same time his Sunday best. In the name of God, what was he to tell Sara? Only last night they had been so jubi- lant over reaching the fifty dollar mark jp their savings account.. Now. . now. He got aboard a street-car and slumped into a vacant seat. Fifty years of work was run- ning thru his mind. Fifty years of toil. Twen- ty-eight of them in the employ of the paint company. And now nothing to show-for them, He brushed his soiled finger wearily across his brow. Once he had nearly bought a home. But that had been when the kids were young, before little Billy had been run over and had his spine hurt. It had taken every cent he made then to pay the doctor bills. Some of the bills had taken years to pay. Nine dollars a week is such a small sum! Of course they lost the house. Poor little Billy’s funeral did that for them. Then Ella grew up such a delicate girl. The damp climate wasn’t good for her, the doctor said. They had borrowed the money to send her to Colorado; but it was too late then. How much was it? A thousand, a thousand... He got off at his stop. No; he wouldn’t tell Sara about the loss of his job. Not for awhile, anyway. Sara hadn’t been the same since that operation two years ago. It wouldn't do to worry her now. Hadn’t the doctor told him only last. week that she might need another operation soon. Perhaps the superintendent was right. There might be lots of light jobs lying around. Time enough to tell her when he had another one. Time enough then. He tried to look his usual self as he climbed the three flights of steps to their two-room apart- ment on the third floor back. Sara had never gotten over that little habit she had of meet- ing him with a rush. It was hard to believe that she was sixty-five. Time had softly with- ered her face, and her eyes still had the little girl look that had drawn him to her fifty yéars ago. “‘ired, dear?” she asked, as he sank into a chair. any depression he might show. “It’s been a hard day today.” She brought him his carpet slippers as usu- al; and then as he was washing up at the tiny kitchen sink, she busied herself in putting the evening meal on the table. There was baked potatoes, creamed carrots, and new onions. Bread, of course, with—no, not butter; it had been years since either one of them tasted but- ter—Gem Nut: something just as good; and a cup of Postum for drink. While they ate she talked of this and that. Of the old couple on the floor below. Poor Mr. Grey was still look- ing for employment. Mrs. Grey was so de- spondent. Their money was nearly all gone. It must be awful to be out of a job. “Aren’t we lucky you have steady work, Tom? What would we do if you didn’t?” No; he wouldn’t tell Sara just yet. Better wait. Wits (0% He helped, as was his custom, wash the dish- es. Thank God, tomorrow was Sunday! He would have a day in which to think things over. In the morning they went to church. It was a nice church. There was a stained glass win- dow with a picture of Jesus as a shepherd minding a flock of sheep. And below it a mem- oria] of a rich communicant who had died and left the church some money. All during the service his eyes brooded on the picture of Jesus —Jesus caring for his flock. With every nerve and fibre of his being he was praying: ‘Lord, help me find a job. PO. ee Mr. Grey came in during the evening. “Two weeks I’ve been looking for a place,” he said, “but things are awfully slack.” Tom tried to cheer himself up by remember- ing that Grey was a sufferer from chronic rheu- matism or something and could only take cer- tain jobs. Perhaps he himself would have bet- ter luck. He would take anything. any- THIHE. 4. In the morning he arose as usual and start- ed off as if to work; but once beyond his own street he loitered uncertainly. It had been so long since he had had to search for a job that he was at a loss what to do next. Finally at a down-town ‘news-stand' he’ bought 'a° morning paper and scanned the want ads. His heart sank as he read them. “Wanted: Old Man to Work for Keep.” “Wanted Elderly Man to do Light Chores for Room and Board.” There were scores of such advertisements as these, but they were of no use to him. At last he found one that seemed to hold out some promise. A department store only two blocks away was in need of a middle-aged man as porter. Just the thing the superintendent had advised him to get!- He felt his spirits lighten. “Oh, you'll have to see Mr. Jewett,” said the head clerk to whom he applied, “he does all the hiring. He won’t be down until ten, tho.” Ten o’clock came. Eleven. Eleven-thirty. He asked the head clerk timidly: “Is Mr. Jew- ett in yet?” “Mr. Jewett has phoned that he won’t be down until after lunch,” said the head clerk. “Better call back about two. You'll catch him then sure.” With his spirits no longer light, Tom sat down on a bench by the Civic Center and ate his lunch. At two he went back to the de- partment store. Mr. Jewett was a fat, pros- perous looking man of about forty, with two chins and a cigar that jutted aggressively from a corner of his pursy mouth. “Sorry. Nothin’ doin.’ You're too old.” “But I’m pretty strong. If you would give me atrial. . .” “Good day,” said Mr. Jewett politely. “Close the door as you go out.” On heavy feet Tom dragged himself back to the bench by the Civic Center. He bought an early evening edition. A contractor was ad- vertising for twelve pick and shovel men for an excavation job on Broadway. He had to take a street-car to get there. That cost seven a The foreman looked him over scorn- ully. “We want young men, eld timer, young men. He went home exhausted; so tired he could hardly eat his supper. “We're getting out a rush order of varnish, Sara,” he told his wife. “The work’ll be easier again in a couple of weeks.” As the days passed without better desperate. One pay day Sara that the firm had luck he began to he got over by Swell their savings. By Henry George Weiss “Yes,” he said quickly, glad of an excuse for decided to pay the men every two weeks wf stead of every Saturday as formerly. But the second week drew to its close without one sign of a job. There was only one thing to do if Sara were to be longer deceived. Taking the bank book he went and drew thirty-two dol- lars and some cents from the savings account —the amount his wages totaled—and took them home to her on pay day. Fifteen dollars was laid aside for the rent that would soon be due. Five dollars, Sara figured, might go to The rest would be need- ed for general expenses. For the first time it seemed a blessing that Sara’s sight was bad. She never looked in the bank books herself, but always had him read the figure to her. wnt The night he brought the money home she had news for him.: The Greys had been given orders to move! Mrs. Grey was nearly crazy They had no food in the house. She had lei them have some. Wasn’t it terrible? And To with ‘an awful fear clutching at his heart said that it was. Sunday was like a nightmare. He went out Monday determined to find work if it could be got: Someone had told him about the Free Employment Agency on Tenth street. He gave his name to the man at the desk. All day Monday he stood and scanned the black- boards. And all day Monday only two notices decorated them. BLACKSMITH FOR LUM- BER CAMP and JAPANESE BOY FOR PIED- MONT HOME. Nothing else; though he stood there all day. Sometimes employers came look- ing for help. Mostly foremen wanting laborers for construction jobs. Their eyes wandered over him unseeingly and picked out the young- er, huskier men. Even the part time jobs were beyond his get- ting. He was a little deaf and couldn’t always hear when the clerk bellowed out. More ag- gressive men, mostly younger than himself, were always to the fore and got them. Then there seemed to be a system. He noticed this on the third day. Certain men took nothing else than the part time work, and were favored by the clerk, who called out their names as fast as the short jobs came in. Several times he was summoned to the office to’ séé pros-" pective employers; but always he was too old for the job or they wanted to pay him nothing but his board. Everywhere he went he was too old, too old. And as the knowledge war forced on him that to be old on the labor mar- ket was the one unforgivable crime, shoulders sagged more than ever, his eyes took on a haunted, terrified look. Only once did he try to fight against the dictum of an employer with open protest. “But good God, man,” he had cried, “I’m not too old to have to eat!” The third week of his hopeless search passed. As always he tried to be cherrful at home. Of course he did not always succeed. But Sara put his strained, harassed looks down to fatigue. : ‘Tll be glad when they get that old order out,” she said. When he came home the third Saturday she was in tears. “T’ve just come up from the Greys,” she said. “O, Tom, it’s terrible! They couldn’t get ou } you know, because Mr. Grey was sick and the: had no place to go anyway; so the landlo called in the authorities, and they’ve arranged to send them to the poor house!” The strength seemed suddenly to go from Tom’s legs and he sat down quickly. Sara went on passionately: : é “I'd rather die than go there! They havea | women’s ward, and a man’s, and they’re not allowed to be together. Think of it! After all those years, to be separated. Isn’t that cruel? dread die than be separated from you like eve Tom got up suddenly and took her im his arms. “Don’t worry, dear, we never will be.” She whispered: “Oh, I’m so glad you're working!” ‘ He went down to say good-bye to the Greys. It was a terrible experience. The next morn- ing he looked at the face of Jesus the shepherd on the stained church window. “O, God,” he prayed, “I’ve gotta find work. I’ve gotta.” But Monday passed, and Tuesday. He walked himself to exhaustion making the rounds of the outlying factories. W came and went. Soon Saturday would be here, and Sara would be expecting another thirty-