The Daily Worker Newspaper, April 24, 1926, Page 13

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

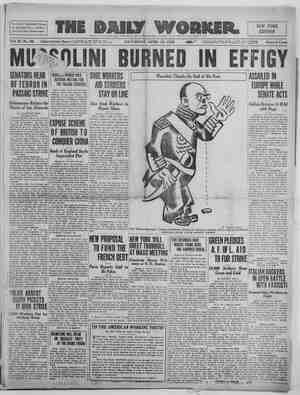

ae Psychology of Revolution By D. Kvitko. THIRD ARTICLE, THE PSYCHOLOGIST ON HIS HIND LEGS. OM the sources of Professor Mc- ™) Dougal,’ the well-known English Psychologist, many draw their psycho- logical wisdom. It is curious, there fore, to learn what this representative of bourgeois psychology hag to say about revolutionary mass action. This , Savant differentiates between a “sim- ple crowd” and the army. The differ- ence between them, he maintains, lies not only in the discipline, but in the education and traditions received by them. The “simple crowd” stands on the lowest rung of the ladder of cul- ture and judgment. The reason for this is that those ideas which are grasped by the crowd must be ac- cessible to the mind of the most back- ward and unintelligent member of the throng. Thus the most unintelligent person brings down the standard of intelligence of the rest of the crowd to his own level. Even intelligent people act differently in a group because of the variety of their education and cul- ture. In mass action only the primitive tendencies, common to all, come to expression. Another reason for the in- terior intelligence of the crowd, ac- cording to McDougal, is its “suggesti- bility.” The throng impresses each participant with a feeling of myste- rious and invincible power. It cannot resist prestige. The most intelligent person as member of the crowd ioses the faculty of criticiam. And when the orator makes a motion and the crowd applauds it, the intelligent per- son is also caught by the whirl of applause, though in normal times his attitude would have been of a critical nature, In mass action the sense of per- sonal responsibility vanishes, and this intensifying one’s emotion, diminishes the possibility of reflection, especially when it concerns general action. The sense of responsibility falls in propor- tion to the number of participants, for every participant of the mob feels fhat he is only a small part of the whole, and therefore his respénsibility is very insignificant. Another reason for the low degree of reflection of the individual in revoltuionary action is the diminution of personal interest and attention, and also of the lack of observation. Such is the character- istic of the individual in the crowd. The appeal to the intelligent person to refrain from mass action is too well evident, for to be an insignificant participant in an act in which one nearly loses personal identity, becom- ing a beast, is indeed of little attrac- tion, But is this evaluation of the indi- vidual behavior in mass action cor- rect? Let us stop for a moment on this point. If the leader had no pres- tige in the eyes of the intelligent indi- vidual before the latter joined the crowd; if the individual were capable of criticizing him before he joined the | Henry’s Tin Goose She lays the Golden Eggs, says Henry Ford,—but It isn’t true; the profits By William Gropper are really the stolen product of the labor of Henry's slaves, iinet. crowd, then why should not he be able to do it in the crowd also? How does controversy in a gathering take place; how division into opposing groups occur? No, the revolutionary mass is not the simpleton, the bour- Beois psychologist characterized it; nor is the patriotic army as wise as McDougal depicts it. True, the orator must employ popular language ad- dressing a motley crowd; but since the ideas he expresses, or the meas- ures he proposes, are of a general na- ture, the advanced and the backward in the crowd are equally interested in the same proposition, whatevér lan- guage may be used. Precision, clarity, brevity are required then. To one with critical training demagogy is de- tected wherever it is. The mode of public argumentation must be differ- ent from debating in a small circle. Since personal responsibility is di- minished in mass activity, according to Mr. McDougal, why should emotion which is called out only when danger is imminent, or our innermost sym- pathy is enlisted—why should emotion be present at all, unless one igs inter- ested in the thing? And does not emo- tion take place in personal affairs, too, if the occasion calls for it? Wherein lies the difference? Can a person be suggestible when he joins a throng to which he is either inimical, or indifferent? While people around him are excited, the stranger is left cold or is annoyed or cynical. Could the leader carry prestige with him? Evidently—not. Well, that means that one does not always forget about his own convictions if he had them beforehand. As a rule when one is in a crowd he indulges in an event of a general nature in which as a social being he is interested, though differently. In proportion to the inter- est in the social affair one has taken before he joined the gathering, he concentrates his attention on it; and in each case, as the occasion requires, on one particular thing. But once it is @ matter of;concentrating one’s atten- tion upon a particular thing, the rest must be in the “fringe” of one’s con- sciousness, not in the center. If one’s mind is shut off to the rest of the world while reading a book, and atten- tion is fixated on it, the book is no less suggestive than the crowd orator. The degree of suggestibility depends upon the person. The author’s pres- tige has the same effect as the orator’s. Of course, while reading a book, ac- tion is impossible; the reader’s emo- tion is then fruitless. Prestige in mass action depends upon the pre- vious amount of knowledge, expe- rience or interest, the individual pos- sesses. And if action is necessary and one kind of action is required, the in- . dividual may have to choose between friend and foe, and trifling differences must be overlooked. Pondering and hesitating may harm more than ten- efit the case. The individual gives his undivided attention to the occur- rence and acts quickly, Suggestion, then, cannot take place, Say, with an atheist listening to a Billy Sunday sermon. While the ser- mon will amuse th atheist, the zealot will be carried off hig feet, for the zealot was a believer before he went to the tabernacle, Neither is the sense of invincibility of the. crowd always present. The crowd may meas- ure up the numbers of his and the other sides of the fence and, accord- ingly, retreat or attack, After we acquainted ourselves with the behavior of the individual in the crowd, let us proceed with the beha- vior of the crowd itself. According to Mr, McDougal, its characteristic traits are—fickleness and extremity. The crowd is capable of murdering the same¢ person who was extolled a short while before. It swings in its actions from a wild orgy of murder to a ten- der and touching care. The crowd has not will power, therefore it follows the leader, who makes his appeal in the most elementary way. Why is the crowd both generous and cruel? Why irresolute and hasty in judgment, granting even that the char- asteristics are correct? It only signi- fies that the occasion calls for action of such kind as the individual is not confronted with in normal times, and with which he cannot cope single handed. But is not that a time when one must go further in his action than in personal affairs? That he is not behaving in everyday life in such ex- treme fashion may be explained from the fact that he is powerless and iso- lated from his associates. Another reason may be that he would not have the courage when alone, That is mass action where danger and obstacles are threatening does require will-power and personal sacrifice; “and*‘in’ this respect the revolutionary act is highly moral. Not that the individual is not emotional when alone, but he is not daring enough, or is irresolute, or may consider his isolated action futile, at times even underestimating it. From this discussion it is evident how “true” and “impartial” the de- scription of the revolutionary crowd is. From the “scientific” characteri- zation of the army we shall see next time how well the psychologist serves his master, Passaic By ADOLF WOLFF. PAssAIc is the battle field, - Of boss and working class. Our war cry, “We shall never yield!” We vow, “They shall not pass!” Your bloodhound thugs can bark and beat, And throw us into jail, But bravely their assaults we’ll meet, Their dirty work shall fail. We do not battle for the Lord, But for a living wage; This drives the greedy master horde, To curse and fume and rage. In this great war for human right, Alone we do not stand, All are concerned in this brave fight, All workers of this land, Should we be vanquished on this field, By the army of black Greed, Then workers everywhere must yield, To those who make them bleed. Workers, join us in this fight, . . It’s yours as well as ours. We'll win if we will all unite Against the ruling powers,