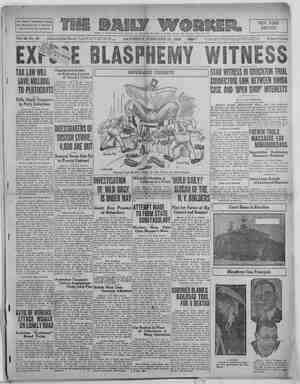

The Daily Worker Newspaper, February 27, 1926, Page 10

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

\. “A GOOD CITIZEN” - QMITH was an old man. His body was bent forward as if he had carried a burden on his shoulders all his life. His arms hung loose- ly down his sides, with hands like weights. Gray hair covered his head. , The skin on his face was grayish and dusty, and it gave one a barky impression. His eyes were sunk far in his head, and were framed with almost visible bones. Out of them shone no light, no hope: There was a look of patient obedience in them. There was an air of harmony between his humble soul and his crooked back. He was satisfied with his lot. For many years he had worked as garbage: man at the Constitution Hotel. But now,it was different: He was no longer garbage-man. He was boss: He recalled the days when he had been a jack of all trades around the place. That was long ago, in his younger days. .The hotel had grown enormously.. Now there were jani- tors around, scrub women, polishers, women who dusted furniture, men who cleaned rugs with vacuum cleaners, innumerable _bellhops and waiters, and a doorman who was dressed like a king. There was also a man to help, car- iry!out the garbage. Of this Smith felt proud. He was boss. Why shouldn’t one feel proud? One had a steady job, nothing to worry about. The work one knew by heart. So many cans full, so many cans to empty. It was easy. When Sun- day came one went to church. And there was the kind man, the servant of God, who knew all and loved all. One should work and then pray, and then everything would be glory. One would be saved! Smith was glad. He worked and he prayed. QNE day Smith was called into the manager’s office. An employe had died and there was a job in store for an honest man. The man- ager had ‘decided on Smith. He had carried garbage long enough. The manager had gath- ered riches while Smith had gathered garbage. Someone else could carry garbage. Smith shouldn’t have to break his back any more. It would be easy for him to keep the convention room clean. All one had to do was to pick up papers thrown around, dust the chairs, anil keep the spittoons clean. Only, one must do his, work quietly and go about in silence. One should perform his task and leave like a shad- ow, without a sound. There were big men who required attention without disturbance. Smith was overwhelmed with joy. Had the manager been a statue he would have kissed his feet: Had the manager been a>child, Smith would have embraced him in his arms, but as he was a middle aged man whose diameter in- creased every year, Smith did not dare. He was irresolute as to what he should do to show his appreciation. He worried himself so that he could hardly stand on his feet: ‘ He tortured his soul by making himself think that he had been the.worst.sinner that had ever lived and that the manager was god almighty. And in his Jowliness he clasped his hands and bowed before the manager, not daring to look him in the eyes. Before he went to bed that night, he fell down on his hands and thanked the Lord. He idolized the men for whom he kept the convention room in shape. But he could never understand these people. ‘There was Mister Pork, for instance. An awfully big and heavy fellow, having a fat cigar wedged in between his lips. Then there was Mister Pigsteel, a most pectliar man. For hours he would talk about iron and steel; and one day he declared he had sent a telegram to the east for a ship- ment of hands. Hands were cheap in the east and it was worth while to pay the freight. Smith wondered what. kind of hands Pigsteel referred to. -Were they mechanical hands, or was he talking about human hands. In his ig- norance, Smith looked at his own hands. He didn’t know. Another time there was an auto- mobile accident outside the hotel, followed by an agonizing scream from a woman who must have been torn in two. The shriek echoed thru to the convention room, but Pigsteel puff- ed his cigar and never moved. He was think- ing of the market prices. Another nice man was Mister Oilbarrel. Onte this kind-hearted soul gave Smith a cigar. Such a, big one! And how good it s elled! It sure- By Werner. Wehlen' ly ‘must have cost a dollar at least. What kind of work did one do who could afford cigars like that? One was no mapsieecagte That was sure. After this Smith was overjoyed when he found smoked cigar stumps on the floor. The short stumps he chewed right away; the long ones he took home and saved for Sunday e¥e- nings. A Mister Pork, in a speech one day, mentioned Smith, who was walking around with a dust rag and mechanically picking up newspapers which had been thrown around. It was good citizens—like Smith—one needed now. Good men. Men who could make themselves use- ful. Dependable souls. Christians. Honest to God fellows who believedin Jesus. Men should be satisfied. The Lord-provided for everybody. All men were born free and equal. This was America: a great country, a free country. People came here from all over the world. They came here in rags, and they came here hungry. But they were clothed, and food was set before them. They were given a chance, an opportunity. There were men like: ‘Mister Pigsteel and Mister Oilbarrel, not to mention thousands of others, that provided for these stranded souls. Jobs were given to them in factories, mines, shops, all maintained for that purpose. One should be thankful. One should try. to see. Try to understand. Smith was happy. He saw and he understood. ON his way home that night, Smith happened to pass a street meeting. His old bones caused him to stop for an Instant and he heard the speaker thunder forth: “Man was born free and is everywhere in chains.” What a lie! Such a fool! A bum. Look at that fellow’s rags! Why didn’t he get himself a job? Talk- ing like that! Who wasin chains? Why didn’t he go and listen to Mister Pork? There was a man who knew something. Or why didn’t he go back where he came from? This was no place for talk like that. Chains. Imagine! What in hell did he know anyhow? One couldn’t help agen at an idiot like that. He ought to be in jail. . 39 Hiss i .Debis Capital and Labor in the United St: By A. A. PURCELL (British Fraternal Delegate to Last A. F. of L. Convention) HE first superficial impression 1 got from the United States was one of the extraordinary obsession with bigness that runs thru the whole of social and industrial life there. Everything is “million dollar”—every- thing is.on the grand scale. This aft- er all is natural enough; for in the United States we have capitalism in its most gigantic, most advanced, most powerful form. That America is the home of trusts and combines, of the most highly de- veloped stage of capitalist monopoly, is a commonplace. But I doubt if all the implications of this fact, and more particularly its meaning for the work- ers, are fully realized by those who have never set foot in the land of the ree, There has been a good deal of oose talk going on for some time about the high wages current in Ame- rica, about the superior conditions of life of the workpeople, the number of workmen who own their own motor cars, and so on. We have even heard this talk. inside our own movement, using the example of America to dem- onstrate the advantages, to the em- ployers as well as to the workers, of high wages. ' What struck me, as a workman, most about the various works and fac- tories I visited? “I was not concern- ed with their perfection of industrial technique, remarkable in itself tho that is. No, what impressed itself unforgettably on my mind was the spirit of vigorous regimentation, the extreme division of jabor which makes a man a mere automaton, per- forming one monotonous mechanical operation year in year out. The Ame- rican industrial regime, in spite of ifs boasted high wages, is even more than its British counterpart, a mono- tonous tyranny, in which the worker is regulated and ordered and disciplin- ed and controlled to the last possible degree. . American industrialism is nothing more nor less than a slave system; its so-called “benevolence” towards its workers being merely incidental to the great task of extracting profits— and fabulous profits, too—for plutoc- racy. An ironical fact worth noting is that its keenest advocates are em- ployers, servile writers and the like— not workmen. It is easy enoigh to talk glibly about the “advantages” of America when you don’t have to bene- fit from those “advantages” yourself. A point into which I inquired with some care was the question of high wages. Here it was particularly help- ful to get the evidence of English workers who had emigrated in the course of the last-few years. They all told me the same story. Tho their nominal. wages were higher than they would be getting in England, the cost of living was so high that their ,real wages were about the same; in some case even less. Special stress was also laid by all my informants on fe terrific pace and intensive charac- ter of the work. So severe is the strain that men are, on the average, worn out at forty years of age— whereupon they promptly get the sack; another sidelight on “penevo- lence,” It must be remembered, of course, that there are exceptional trades where the wages are extremely high, The chief of these is the building trade;-where skilled workers such as painters, plasterers and bricklayers command at the present moment in America a high “scarcity value”; their wages may be as high as £16 ($80) or more a week, But this is excep- tional, My previous remarks about the. ex. treme regimentation to which the| workers are subjected. need to be sup- plemented by some observations on the most all-pervading and one of the most significant features of American industrial life. I refer to the spy sys- tem. It is no exaggeration to say that in America the spy system is as wide- |] ————. spread, as usual, as powerful and as integral a feature of industry as in- surance is in this country. Which is not surprising, since spying is of its nature a form of insuranceagainst strikes, against trade unionism against any militancy whatever o the pet of the workers. Spy companies, such 4s Pinkerton, Baldwin-Felts, W. J. Burns and a score of others are themselves vastly wealthy and powerful corporations, living like parasites on the general body of capitalism. Even if employ- ers find, as a number of them are finding, that to employ spies is play- ing with fire, they cannot escape. The spy company has them in its clutches, and it blackmails them into continu- ing their “patronage.” In addition to sending spies to work, as ordinary workmen, in the factory, Burns or Pinkerton or the others will have their “men” who worm their way into the trade unions, and ‘haves been known to achieve prominent positions in the movement, which they were able to employ with deadly effect. I have met men who have been spies and they made no bones about it— any more than they did about _the ‘guh in their’ pocket.” An American writer in this maga- zine, *Mr, Heber Blankenhorn, de- scribed the labor spy system as “be- gotten by unrestricted capital out of restricted labor organization.” He continued: — : The tendency of American unions (not without parallels abroad) to- ward being craft cliques bore its part. in begetting espionage. Not only did this leave outside the un- ions masses of workers to be the battening ground of disorganizing spies, but, within the unions, cliques, with their undemocratic practices, invited spying. When “getting” the official clique’ meant getting the union, employers were likely to avail themselves of the Opportunity. ° *The Labor ee August, ware vol. 3, Ng. 2, pp. 94-102. comparison with, say, our Own trade .| made a plea for American support of It is no use blinking the fact that in union movement, the American move- ment—by which I mean the American Federation of Labor— is extremely backward. It is organized on the most rigid, narrow, exclusive craft basis which makes even the unfortu- nate craft distinctions that still exist in our own movement pale into insig- nificance. Its . attitude towards the sixteen or twenty millions of unorgan- ized immigrant workers is a more aloof, more hostile re-edition of the attitude of our “new model” craft un- ions towards the unskilled workers sixty and more years ago. Its atti- tude towards the masses of Negro workers, with which I deal in detail beloW, is even more ‘hostile, The American Federation of Labor does not pretend to be other than an organization of the skilled white “aris- tocracy of labor”; it is in the literal sense of the words a “minority move- ment,” orga@izing only a small mi- nority of the industrial workers of the United States. I do not need to dwell at length on its various char- acteristics which seem so reactionary from our point of view—such 4s its} opposition to nationalization and to in- dependent labor political action. These points are sufficiently ‘well enough known here; it is essential that they should always be borne in mind. To a British worker it comes with something of a shock to observé that many prominent»officials of the American Federation of Labor and its affiliated unions are republican or democratic members of congress, Im- agine our feelings if, nowadays, Bri- tish trate union leaders sat as liberal or Tory M, P.’s! It was to the annual convention of the American. Federation of Labor that, speaking as fraternal delegate from the trades union congress, I and berty. convention resolu eda racy. . . > racy. Now I "tnd «| frankness and s rican friends s! this talk about? plete humbug. the spy? & erton International Trade Union unity, That Plea was rejected by President Green “Monry| among other things: - The Americans stz Neithe ternational of autoc nor any other intern complacency ignore of American labor pol labor is friendly to ‘In so far as the worl -achievement of the ; It will conte every inch of grounc wherever autocracy § the hallowed soll « phere. And we &h pretence of “world | a mask for invading ‘destroyers, The New cated to human égee dE racy” is, in my bumt ‘Den of the frame-up, “Democrac Rockefeller and \ and Baldwin- racy”—in the land wh ings and the bludge der of workmen 8 in his declaration tha Federation of Labor w with labor movement: —that rest on soun principles of democra righteousness : The same poin? Jas oe