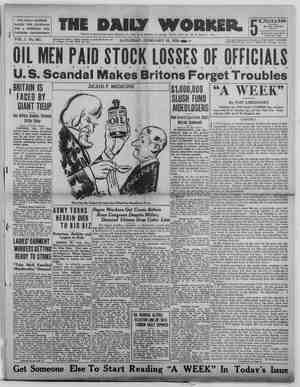

The Daily Worker Newspaper, February 16, 1924, Page 12

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

Boris Pilniak, the Greatest of Russian Writers By VICTOR SERGE. (Note: In a later issue of the Magazine Section of the Daily Worker we wil print one of the most remarkable of the _ short stories by this young Russian whom Trotzky rates as the great- est of the writers produced by the revolution, The story has been translated by Louis Lozowick who is an authority on the latest art and literature of Soviet Russia and who will continue to translate and write for. the Daily Worker.) * Pause is decidedly the most tharacteristic and the most cele-! brated of the Russian authors. His first work appeared in 1920 in the Moscow state edition. He writcs, exclusively about the Revolution. He has written a novel, called, “The Bare Year,” as well as a couple of volumes of short stories: “Tales from Petrograd,” “Ivan and Maria,” which | embrace the whole of the Revolu- tion. Pilniak’s manner seems strange | at first. But it is in absolute har-| mony with the spirit of the time. | He writes rather in the style of, futurist painters. It would be ut-. terly impossible to describe the Rus- sian Revolution in the style of a Balzac describing the sordid and mo- notonous life of a father Grandet, as well as with the utter indifference, the finish and perfection of style, with the absolute harmony of the whole of the detail—which we wit- ness in Anatole France’s—“The Gods Athirst.” It is only the writers of the time to come that will be able to describe the Revolution. We, as well as Piiniak, are incapable of doing go. The Revolution, which has done away with so many forms of the past, has alike cleared up many e literary prejudice of the past. It is hopeless to look for a cun- tinuity of events in the work of this author. Intrigue (how pitiful this expression) does not exist. io chief and secondary figures either, in his work. The movement of masses in which every single figure is a world for himself, representing in himself completion. Events rush- ing in and overpowering one, nu- merous human lives intermingling, each of which always represents in itself an occasion never to be re- peated. The whole of them, in the end, of not much importance on the ba-keround of “Russia.” the snow- drift and Revolution, for the coun- try, the snowurift, and the masses, are the only things remaining and stable. The exterior aspect of Pil- niak's work corresponds to the con- tents of it. The pages often wear a somewhat strange aspect. One page carries the description of an old priest among his ikons, breaking under the burdens of his sins, Sud- denly the narration breaks up and one hears the people in the street passing , talking; a new inter- ruption, and in comes, tearing along. a hungry, howling wolf with bared teeth. This constant change of de- seription and pictures requires, of course, different aspects of the page. The reading of this book is, in a certain sense, rather bewildering. But the final impression is strong and powerful. Pilniak is under the influence of the masters of latcr years, such as Andrei Biely and Alexei Remizov, but he resembles them in manner only, and not in contents, He has such a lot to show and to describe, and to bring out in his book, that every manner and forn: is oppressive to him. He lets life drift where it will. Classicism is of value, but in shapes long existing. In the “Bare Year” we find eight beautifully treated subjects: the lit- tle bourgeois, the dying aristocracy, the sectarians, the anarchists, the monastery, the train number 57, the peasants, the bolsheviks, But the same stern unity reigns over all on eccount of a totality of the varying d as in some heroic sym- phony. In the course of the story “Ivan end Maria,” the shouting of a ¢niner, whe has nothing whatever te do with the story is repeated, a blavk slave of international metal- lurgy, who quite inert and apathetic frora his work seeks his couch ior} W. his nightly rest. But what a numn- ber of idyllic and psychologically fre novels woud require just such a refrain in order to bring them back to the actualities of life! The LEITMOTIV of the whole of Pilniak’s work is the snowdrift, the most Russian of things. Pilniak's style is often extremely musicai. SR re rrr The author leaves nothing unob- served, he is anxious to communicate and give back everything he sees, and everything that impresses him. In a word, dynamism, simultaneous- ness, absolute rythmical realism, these are the dominant features of his literary form. We must not forget to mention his hove of exact detail, of the minutest description of customs, of the sentence caught up in the street, all of which are simply given back without any par- ticular commentary, exactly as some historian would note it, Pilniak’s interest seems to con- centrate itself chiefly on the man- ners and customs of the Revolution, and this chiefly in the country and the provinces, The general play of action of his stories, is the small tewn (Riasan the Apple. or Ordynin Town) in “The Bare Year,’ which he really does seem to thoroly know. What is the chief thing that he ov- serves? The swamp of the pass. In the small, provincial town the these are the Bolsheviks. In the morning they used to meet in the convent (strange times indeed!). Men not unlike leather, in leather jackets, almost ali of them tall and manly looking, handsome and strong with hair curling out of their caps, pushed deep into their necks. Each of them had an excess of will in his tensed muscles, in the expression about the mouth and forehead, in the soft and decided movements of the lithe bodies, heaps of will and audacity. Here we are before the elite of the Russian people, one of the oldest in existence. And it real- ly was a good thing that they used to wear leather, because thus the sweat lemonade psychology could not soften them. The whole of their bearing said “we know well ‘what we are about, we have made up our minds.” Here is one of them described more particu arly: “Archip Archipov used to spend’ his days in the Executive, in writing, and the evenings about town, in the petty bourgeois leads a life mnot| factories, lectures, and meetings. He much better than that of a pig, tween hig counter, the well laid table, and the warm, sweaty, dirty bed under the saints’ pictures. He igs brutal towards the weak, hard and of unbending will towards the op- pressed—servants, women and. chil- dren; self-satisfied, egotistical, ig- norant, heir of a thousand simiiar years. War took the the young men out of the swamp of the small towns. “As Donat came back, he had learned nothing new, but the old was not forgotten, and he wanted to destroy the whole of it. He came in order to create.” He hated the old, The dread of it occasioned by the mighty shock of Revolution is one of the chief reasons of Revolution. In this stagnating swamp of the times gone by the former rulers are abandoned to ruin on account of their weakened spirit, and their poor blood. In a word, it is an histo- rica] judgment that weighs ovcr them. The ~ princes Ordynin (whose fathers once founded the town of Ordynin) are at present syphilitic and are approaching their end. The old father is waiting for it, surrounded by his ikons, and prac- ticing self-castigation. Egon is a drunkard, stealing and _ selling his sister’s last clothes in order to drink (this is the year 1919). ‘ Chapter VII of the “Bare Year,” called, “without a tit.e,” consists but of three words: “Russia, Revolution, and snow drift.” The beauty of Rus- sia’s landscape blends with the drift of Revolution. One never knows how to discern them in Pilniak’s stories. I do not think that it is even neces- sary to do so. Pilniak compares old Asiatic Russia to the Russia of to- day, which he sees rising out of the drift, and we must admit that he sees it-extraordinarily well, and that} you is his chief merit. Listen to this conversation taking place in a rolling tram . . . “In a hundred years people will speak about the actual times as about the period of life when the human spirit rose to a glorious standard well, but my shoes are very worn, I really would like to go on a trip abroad, to eat in some good res- taurant and to drink a _ decent whisky.” These are the terms in which a young engineer is thought- fuily speaking in Pilniak’s book, quite like reality in new Russia; it is not the engineers that are life’s masters. This leads us to the bol- sheviks. Pilniak flatters the Revo- lution just as little as the revolu- tionaries. The gloomy pages as well as the nightmare ones are indeed not scarce in the course of his work, You see in his book peasant women paying with their own and biood for a place in a filthy train full of bugs, a typhoid fever trans- port train, escaping out of the fam- ine region. A little further a hys- terical Chekist, shooting down her lover. : ing coffins for the whole of their family in advance, as they are quite sure not to be spared either by famine or typhoid fever. The book contains pages full of terror, one is, however, not quite sure whether the accents of it are real or preientd, estern people are yet not fully aware of the martyrdom that Russia underwent. Pilniak seems to be quite well informed, and writes it down accordingly with the blood of his heart. His constant aim is to be as close to exact truth as pos- sible. In the drift there is but one kind of people that remains upright, and be- | used Peasants are described buy-! to write knitting his brows, holding his pen almost like an axe. In his speech he used to pronounce the foreign words incorrectly. He ‘was an early riser, and in the morn- ing he crammed and crammed as much as he could; algebra, political economy, geography, Russian his- tory, Karl Marx’s Capital, he had a German grammar, and a diction- ary of Russianized foreign words by Gavkin. Father Archip, on receiving the information of his having cancer, condemning him to awful sufferings and unavoidabie death, goes to his son, and talks to him about it: “do you believe it to be a wise thing to make an end of it?” he asks him. An impressive scene follows, “I be- lieve I'd do it if in your place, father, but of course you must act as you think best.” “Live, my sen, go on working, marry and bring up chil- dren.” Not a word more is wasted on this oceasion, both remain decided and sure as to the next thing to be done; the one for going on living, the other to blow his brains out. Everything in Pilniak’s works is tense and painful, except a lighter passage fohowing this stark one. A couple appear in it. A Bolshevik couple, strong and simple, both of them, and of an extreme inner hon- esty. The man Archipov speaks to the girl called Natalia, whom he wants to have for his wife: “I am always in the factory, in the Exe- cutive, quite taken .up by the revo- lution . . . asm young man I have had some love affairs, I have sinned with women; But it did not last. I have never been ill, We shall work together. We shall have handsome children. I want them to be sensible, well, you know, besides are educated than I am. ‘But I won’t give up studying. We are young and healthy.” Archipov hung his head. She consents with no less simplicity. One might be inclined to think that these revolu- tionaries are afraid of, and trying to avo}! the passionate impulses that burn in a couple who are about to mate ., .. “Yes, children, that is the chief thing, but I am no longer a young girl. The man shrugs iis shoulders. Chief thing is to be human.” Cleanliness, reason! “Love or no love,” she goes on speaking, “we will have an intimacy of our own and children, and then work, work, my love! There will be no lies betwen us, no suffering!” Archip turned silently back to his room. The word intimacy was not mentioned in Gavkin’s dictionary of the Russianized foreign words. Has the author, perhaps, been trying to idealize the Bolsheviks? It does not room. The word intimacy was nat the will to establish a new form of life is their dominating trait. Surely Boris Pilniak has _ seen other heroes than those during the revolution in Russia. But the Bo!- sheviks are the most deliberate ones, conquest is in them, simplicity, rea- son, conscience, will In the meantime the Russian an- archists are gpm: Ae passionate philosophy of strength, “who are free under a black banner,” working in the fields of a confiscated prince's estate, at the same time. during which the Revolution was fighting on its whole front. They do not at- tempt to seize the leadership in Revolution, but they drift along, waking use of it wherever they please. “Natalie had again a feel- ing ef the Revolution carrying her| off to some region of joy where, however, sorrow was always follow- ing every tempest of joy.” . . . They work, work, love. dream and ‘fight. And their adventures end, as has often been the case in the Uk- raine. When the old emigree, Harry, asks for his share of money, which was seized in Ekaterinoslav, Youzik refuses to give it. Shots are fired in the night! Free people murder others no less free. They have mur- dered the shandsome young woman because of money, they have mur- dered the woman who has tasted tne violent joys of Revolution. And thus the black banner turns to~be the shroud of the young dead thing. The Soviets send a troop of soldiers who -occupy the forsaken commune. Somewhere Pilniak writes: “I re- mained in the free commune Peskis up to the day when the anarchists killed each other.” I wonder whether I have succeed- ed in pointing out the strong realism of this new author, the strength of whidh is sometimes so overpowering that the immediate impression of things and particulars stifles the to- tality of the impression. This real- ist has a cult of energy and strength of man, beast and even nature. “The strongest among men are the revolutionaries and among beasts of prey.” Pilniak likes to introduce the life of wolves into the lives of men who are in a state of mutiny. “‘ithru wind and snowdrift in the sinking darkness, are the wolves trotting at the heels of each other a grey herd, males and females, the leaders ahead, and soon snow had covered their traces. (Ivan and Maria.) Some of the stories of Pilniak from the years ’18 and '19 are ex- , trematy remarkable on account. of their being radically different from his new things. The oldest ones are exactly in the grey dull tones of Tshechov’s worst period; the drama of the spleen in the utterly unin- teresting life of a little bourgeois woman. The other ones, a shade better, describes the same sensations, as was usualiy done in the pre-rev- olutionary time. Life which had no issue on account. of its utterly in- curable mediocrity. Without the mighty uproar of revolution it is not at all unlikely that the author would have remained in the old cur- rent, and would not have added much to Russian literature. Boris Pilniak owes everything to the Rus- sian Revolution, up to his style even; it was the revolution which gave him the originality of his tal- ent, the insight in the development of things, the broad view with which he embraces boundless Russia, rich in suffering and struggle, the vision of surging strength, the whole of those shings which were quite hid- den to the authors of the old regime. That is one of the chief reasons why one is sorry to find in his writings only an intuitive perception and a primitive admiration of the revaiu- tion. What does this revolution want? A reader must be quite pos- sessed and overcome by this idea on shutting this book. What is the whole commotion about? Is the author capable of giving an answer to this? The lack ot ideology, one might almost say, of convictions, deprives his work of a foundation. But it is precisely for this reason that it acquires in our eyes a quite particular value; because it is the best proof of his ; spontaneity, the frankness of his statements. This work shows both in form and subject, pow deeply the author, who himself admits to be- ing neither a communist nor a rev- olutionary, is fuly permeated by the spirit of revolution, After having finished a commercial school, Pilniak left the provincial nest, in which he spent the heroic years of 1917-1921, but to supply his need in potatoes and flour. The whole of Pilniak’s interest is sacri- ficed to the social life interests. But our opinion is that he does not mis- understand the ,ideas, the influence of which, is but too we.l known to him. The totality of the ideas of a class of society that is struggling, carrying off victory and power, be- comes an enormous factor in the renovating process of customs, this is the idea running thru all of his work. The new author ie not yet in full possession of the whole of his strength. He is us yet not en- tirely cear, he is confused, hasty, bombastic,. uneven, but despite all this, his work is today a beautiful grand song on the revolutionary en- ergy of Soviet Russia., (Transiated from the French hy H. Goering.)