Casper Daily Tribune Newspaper, August 27, 1923, Page 2

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

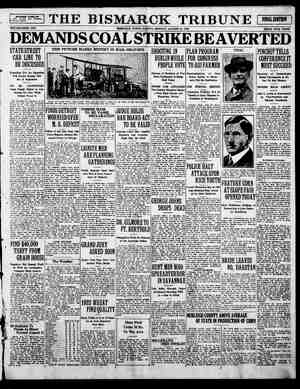

AcE, what do you see in the plate glass window? A pretty face reflected? You are fortunate. The house across ‘the way? Yes. But beyond that, what do you see? Bronzed men, clad only in Join cloths, cowering under the lash of lave driver, tramping clay, C.; a priestess darkening in the Temple of Khons at Karnak, 2000 B. C.; a young patrician oiling his locks, before a pier glass in the baths of Pom- peii, 1 A. D.; the flare of furnaces on a Venetian Canal, 1100 A. D.; a crude factory, in a clearing near Jamestown, Virginia, fashioning baubles for the sisters of Poca- hontas, 1608 A, D.; men, clad in a little more than loin cloths, sur- rounded by machines controlled by an electric button, tramping clay, U.S. A., 1922 A. D. You are looking into one of the oldest of the arts, Alice, for which men have lived and died through 6000 years in order that you might see a perfect world through your plate glass window, or find reflect- ed flawlessly in your mirror—a pretty face. Vanity, vanity, all is vanity, saith the Preacher. Perhaps—but listen to the story of your window and your looking glass. Glass a Blunder, Says Pliny. Pliny set down the invention of giass as an accident, into which a group of Phoenician merchants stumbled while cooking breakfast in the dim days of antiquity. These Phoenicians beached their galleys on the coast of Palestine, according to Pliny. But when they had built their camp fires and tried to set up their cooking} pots to prepare the Phoenician equivalent of ham and eggs, they failed to find any stones in that desert country. So the pots were set up on cubes of soda from their cargo. The heat of the fires melt- ed the soda and fluxed it with the sand, and to their amazement they beheld a clear fluid forming as a result of the fluxing—glass. Pliny Science. Now Science, the iconoclast, steps in and completely wrecks old Pliny. For Science says that to produce the fluxing of sand and soda a heat of 2,500 degrees F. would have been necessary, and that breakfast fires didn’t get that hot, even in hot Palestine, So Pliny, muttering impreca- tions, is led from the witness stand and thrown out of court. One can imagine Pliny, outside, wiggling his fingers at his nose and shouting in low Latin, “You say you found glass in the temples of the Fourth Dynasty, put there in 4000 B. C., heh? Where did those Egyptians get their 2,500 degrees F.?” And, quite unable to answer, a deep blush of humiliation mantles the brow of Science. Solomen’s Marine Grill Monuments built in 3998 B. C. showed glass bottles containing red wine. Beni Hasan, Egyptian Michael Angelo, painted glass blowers about 2750 B. C., and the paintings are still in existence. The Koran, good book of the East, records that Solomon, King of Judah, paved a court with “clear + glass laid over running water, in which live fishes might be seen.” It appears that those ultra-mod- ern hotels with their marine grills are not so ultra-modern after all, The Queen of Sheba, were she to drop in for oysters, would proba- bly yawn, “Ho hum! What a beastly bore. Solomon did all this for me five thousand years ago.” The archaeologists dug a glass boat out of the lava at Pompeii. Scarus, an Aedile, or Superintend- ent of Building, in Rome, con- structed a theatre seating 40,000 in which the second story was entirely of glass. Cherchez la Femme! In the middle ages all the world but Venice forgot the craft of ~ blowing glass, and so to that mag- nificent city it became a secret monopoly that was guarded as life itself. The Inquisition of State prescribed death to glass workers who took their art elsewhere. If mirrors have meant much to women, so did a woman mean much to mirrors, for it was a woman who lost for Venice her world supremacy. Marietta, a daughter of Beroviero, a glass maker of the Fifteenth Century, was greatly beloved by her father, and entrusted with the secrets of his craft. But Marietta loved Giorgio, an artisan, and for love she told him the secrets which he sold to foreigners, enriching him- self, but bringing ruin to the in- dustry of his city. Thrifty American Colonists. In 1450 Venetian glass makers were imprisoned in London by re- quest of the Council of Venice, for plying their art in a foreign land. They were given the privi- lege of working out their fine in their trade, under the eyes of watchful observers. Thus was fae making introduced into Eng- land. The first glass factory in the United States was also the first factory in the United States. It was built in the woods near James- town in 1608. It proved very use- ful in buying up tracts of land from the aborigines, The chief product was glass beads, and they so captivated the fancy of the na- tives that the thrifty immigrants shortly were in possession of all the territory east of the App: lachians. Other glass bead fac- tories sprang up, proving a cheap and profitable kind of mint. One was established near Hanover Square in New Amsterdam to give the Dutch burghers a chance to recoup their fallen fortunes aft- er paying $24 for Manhattan Is- land, A Modern Miracle. In glass manufacture the mod- ern world excels the ancient in ‘} one particular—the modern world produced plate glass, If the modern world had not done this Alice would see more than a pretty face in her mirror. She would see flaws and blem- ishes—not in her face, but in the mirror. And on the avenue, in the shop windows, the beautiful things to buy would not stand out so clearly and so alluringly, apparently sep- arated from the beholder only by the atmosphere. Men realized that windows were to see through, not to see—so they made plate glass. “For now we see as through a glass, darkly,” wrote Paul to the Corinthians. In the days of plate glass Paul would have used another simile. A Cross-Section of Centuries. Plate glass was first made in France in 1688. It is now made best, and in greatest quantity, in this country. It is cast, not blown. Curiously, the making of it in- volves processes which were used when the Egyptians made glass bottles for red wine in 4000 B. C., as well as processes involving the last word in modern machines, In a sense the manufacture of a sin- gle sheet of plate glass provides a cross section of an industry 6000 years old, In a building filled with over. head cranes, electrically controlled machinery of the utmost refine- ment, men walk in their bare feet, day after day, tramping piles of clay. Remove the machines, strip the men, and let the sing of the lash be heard over their heads, the and the scene would duplicate that in the Valley of the Nile before the pyramids were built. Clay is the only practical ma- terial for the making of the pots, which must stand-a heat of 3,000 degrees F., in which the substances which go to make up plate glass are melted. And up until a few years ago the only practical meth- od for reducing it to velvet smooth- ness, free of air pockets, was the tramping of bare human feet. Each pile is tramped for sixty days—one reason plate glass is expensive. In some of the more modern plants, however, this process is now done by a “pug mill,” or mechanical tramper. “~~ Making Haste Slowly. Nor is there a machine that will mould the pots successfully. They are five feet in diameter and four feet high, and are built up layer by layer by men whose skill matches that of the potters of Mexico. With the pots must also be made tuiles, or clay doors for the melting furnaces. The walls of the furnaces are brick, but a door of brick is not practical, In spite of the time and patience and energy that go into these pots and tuiles—sixty days for work- ing the clay, and three or four weeks for the moulding and dry- ing of a pot—they are good for only fifteen trips into the melting furnaces, Then they must be broken up and reworked into new pots and tuiles. In the pots with sand is mixed arsenic, carbon, and lesser in- gredients. The furnaces hold about sixteen pots at a time. They are heated by natural or producer gas. From small openings in the doors the pots may be seen stand- ing aside, each glowing like the sun through a veil of fog or smoke. Men, dripping wet with sweat, poke long steel rods through these openings from time to time and drew forth glistening threads of liquid glass, testing the brew. A Brew With a Kick. Intelligent electric cranes, di- rected by a touch, run their hardy steel claws into the inferno, bring- ing out the white hot pots. The workmen, their naked torsos like bronze statues, skim the impuri« | ties from the surface of. each, Then the intelligent machines in- tervene, carrying the pots to the casting table, large as a drawing room, on which s: as been sifted. There the brew is spilled, spreading in a blistering golden flood. A steel roller runs over the mass like a giant’s rolling pin over pie dough, leaving a sheet of crude glass above which the heat waves throb and palpitate. The sheet of glass is run through a_series of cooling chambers. Wheeled out of the last chamber the glass is little warmer than the atmosphere—but how different in appearance from those shining walls which reflect the light and moving figures of a ballroom! A diamond in the rough. Polishing the Diamond. Again the intelligent cranes, and the sheet, fifteen feet wide and twenty feet long, is brought to the circular grinding table, and transferred as carefully as if it were made of—glass. Two great grinding discs are lowered onto the surface, and the whole ma- chine begins to revolve, the table in one direction, the grinding dises in the other. An hour of this, in which seven grades of abrasives, from coarse sand to fine emery, are used, and the surface is smooth and perfect. NN Ns Ky ii Yi) Y), Alice, looking into her mirror, may fancy that rouge is used only to give color to her cheeks. She hardly fancies that the delicate powder also contributes to the per- fection of her image as a treat- ment for her looking glass. Yet that is true, For on the polishing table, to which the plate glass sheet next goes, small discs of felt, rapidly revolving, bear rouge against the surface. An hour and twenty minutes of this, a repeti- tion of the whole process for the opposite side, and all that man has been able to learn in sixty centuries to make a perfect glass has been done, The End of a Perfect Glass The cranes lift the sheet again and bear it away. (Brilliant, glistening, it glides through the air, bending and waving almost as sheet of paper. A man at each end assists in directing its path. At times, fortunately rarely, there is a sharp and characteristic crackling which sends the men leaping to safety. In a fraction of a second the whole plate slith- ers into a thousand piercing frag- ments, carrying death to anyone nearby. eGlass Window -——~ we Modern Alice Sees y “4 2 Ai JY Lil THE FINISHED PRODUCT Ig : - BY OVERHEAD © RANESJ Standing at last in its rack, the sheet is scrutinized by experts, who work out bubbles and other defects, Other expe-ts cut it to give perfect sections of the larg- est possible size. It is ready then for the huge display windows along the avenues, for the win- dows of hotels and homes, for desk and table tops, automobile wind shields, ventilators—or, painted on one side with nitrate of silver for the boudoir mirror in which Alice sees a pretty face, FEE eg AAAAA 22Z222L1