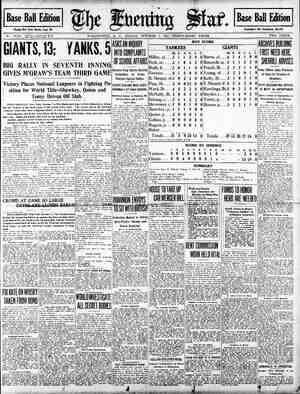

Casper Daily Tribune Newspaper, October 7, 1921, Page 10

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

ts HIS BAD Site Side _ Paes HE Ingrams were on thelr way T homé, and were only waiting in London until it was time to take the steamer from Southampten. Alice Ingram had seen Thorold's name on one of the bills that advertised the two-hunéredth night of his new opera, and on the chance sent'a note to the theatre, asking him to call at the Albemarle the next afternoon. She had not seen him since ¢arly in the spring, in Paris, when he had seemed in a fair way of being spoiled, and the reports kind friends had give him since were not encouraging. noreld was one of the Thorolds of Salem. All of his immediate ancestors had been born in Salem, and had gone back there to be bi in Boston and family had no except s members a tanism, which which had dev in the case of the women into something very like prudery, and which had made prigs of the men. The! screet actions and well-regulated hown articular eris- le good looks chara tics, @y strong a far like! as had their fine prof and when “Archie” Thorola develo to a musical genius he was ed upen with au: of the fam- ne world tion ry early tn istmas rhe age his life anthems and h of fifteen, at which time he was glay- ing the organ in the Episcopal church at Salem. Later, while at Harvard, he wrote the music for the Hasty Pudding theatricals; and two of the comic songs of that production, notably “The Night That McManus Went Broke,” were sung «ll over the United States. Thorold’s elder brothers did not regard as fame, and hoped he would give up writing music of any class after leaving college; but he went oft to Baireuth, and from there to Munich, from which place they heard of him occasionally as being xery busy study- ing thorough-bass. He returned each| “Yes, I came,” he answered, @fter|dren. You make such problems and winter, and went to dances with his|some moments’ consideration, “be- | difficulties; out of nothing. Why, it in sisters in m® ‘perfectly rational and|cause, I suppose, I still believe in| as simple as animal alphabets. A ts ‘acles, and because I had a forlocn|an ape, and B is a bear. ‘That's all! in the spring, ayd when next heard of him I amateurs and some ofc and sung in 2 cantata he had written they dy Maud Anstey’s charming way; nj: he was off again | mi them for a charity entertainment; and &@ romantic opera, called “The Cru anders which he had written both score and book, was nbout to be pro- duced in Paris. met with suc- cezs in London, and later in New York 3 well, and his family finally, on the first night of the opera's production in Boston, experienced the sensation of seeing one of their number leading an “orchestra. looked very young and very much in| ‘o." he sald, doubtfull: though earnest as he leaned forward and beat |he had been weighing lier words and his baton at the violins and scowled)had found them wanting, ‘itis not the at the b ies of the chorus. it was pleast us It doesn't hurt me at all. 7 ns This war a love-song; any one with the most { could make oth rs with any By the time Thorold’s second opera had beeg produced people had grown tlred of saying what a wonder it was his head was not turned, and wanted | dryly. something new to say, so th was such a pity so ni Newed himself and para riled, 's wh be s and had the crit stumbled phei over one another In their haste to ve among the first to recognize the new composer now hastened to point out that the young genius who had awa! ened to find himself famous had neve quite recovered from the shock. ‘Thor- old'had not given much weight to the AN Fa pe. x Copyright, 1981, by The Wheeler Newspaper Syndicate. jlet up on him™ when he offered ex-/to me. Listen to me, Archie. This rooms tonight: and—1 should be ver? {£panish bolero, to which the model |rather the other way. It's about someHe half rose from the chair, but ‘the | went! on. |she repeated. She sat down behind the | Wise, and the boy I know, you will pack | | } had played | electric shock, it might begin to. work | again, | } | | | It was a marked s#oc!al|cannot possibly mend. as well as theatrical event, and Thorold | it 1 after this that he wrote “The Well off} It sounde like somethings! haddearned { and almost }have gone so far now, or I ha’ lifferent voice |S0 low, that I can quite recognize the foeling | force of all the arguments on the other weep or sigh as it\was sung té them. | side, and go the wrong Way without a { , and so did not mind |of her hand and studied him for some cuses. He was standing as sh= entered the that you are only run down and over- room, looking out of the window, and | ¥orked and -nervou: dissatisfied and pale. Generally when | But you canno! Mrs Inness with you; that is, you and are exagger- know, if ghe will not mind my not she noticed how tired he looked and /ating these wickednesses you hint of.| knowing her. Or Pll book uu a box |may be a mood or a pose. or tt may be|giad If you would bring your friend | danced. one, a-nan or a woman, who— How-/|woman touched him familiarly on the “That was very good Indeed,” Thorold jever, Ill aing tt, and then you'll know | shoulder and pushed him down. eaid. “It makes me dry,” the girl answered. t afford to do it too|at the piece tonight, 1f you like, and /*"Did you see about that champagne?” | There was a murmur of delighted in- | he met her he came toward her quickly | often. It isnot @ pretty pose, and were | I'll join you there. Perhaps that would| As he walked back into the dining- | terest. enough, ang held her hand longer than | I not a loiig-suffering lady, I would not | be better, and we can make the supper |room for the champagne, he was dis- tolerate it for a moment It takes a! the “section I have fer you and all my pat'ence not to accept you at your word, and tell my people you are not the sort of young man they should al- was necessary, but today he simply turned and nodded and smiled oddly at her, as though he were rather more curfous to see her than glad. So she walked over beside him. and they stood er Of looking out at the carriages and han- |low thelr daughter to see. But I think soms on Piccadilly we know each other pretty well now, “It Is very nice to see you again,” | and I think there is more overwork and she said. “Tt was just a chance—I saw |late hours im this than anything else. your ‘Seite in large red Waterloo Station as we came in.” He| Bad habits are just as hard to ov was regarding her intently, as though |come at the end as good habits, and he were trying to collect where he | even Balzac's twenty-five years of y had seen her before. “I didn’t know |tu* which cannot be overcome in a da’ whether you could come or not,” she |C&n be overcome in a year. And if you “You are in such demand | Will llve in a bad atmosphere you can- tell me. not expect to be as strong and healthy urse you know very well, u would be if you lived in the| said, with that directness which wai 1 don't think {t {s worse than one his most satisfactory qualities, |that. You have allowed “that I would have come, whether I | stay had had cngageme or not. But I) not agree with you. Don't be afraid to} had meant not to come at first.” ‘Oh, you had meant not to at first!” jrun away, I have a great regard for the man who runs away, If you are tea things, and began moving them about. He seemed to her to be labor ing under a mood or some exciterient, and she thought it to give him time to develop it. “Yes,” he said, slowly and distinctly, “I thought I would not come, becau I dig not want to introduce you to t your things tonight and sail. with us tomorrow, ani +2 all these women | and worldly young men behind you. | Come and play with me on the steame and spend the summer with all you old friends at the old places. where no one thinks you're a great man, and | where you won't see your picture in kind of man you do not ¢ all, the shop windows. That's really “How tragic said. y |what you need. What do you say make you some tea? | Sho stopped and looked at him, bit he “I did not mean to be tragic,” he|made no response, and she hurried on, went on, fmpassively. “It is quite true, |as though to coVer up the fact that I am not at all the man you used to|she had failed to move him. “T can't| know. No one can know that better| understand some women,” she cried, than I. And i had so much liking for you—and for the you used to|mMan because he is good and strong, know—that TI thou would be/|and then they at once begin to pull kinder to’ us both if I Jet you gq home |down the very things they most ad- without seeing me a “But you did come. |mire in him. An@ I cannot understand your sex either. You are such chit- hope that if I could get a good strong | tonic and my conscience could have an | It was just a chance. I hadn't much reasen to believe it would.” | She occupied herself for some little | time with the cups in front of her, and said: “Of course it is very manly and brave in you to tell me this—to say, ‘Here I am in a very bad way, and if you cannot help me no one can.’ That makes it so pleasant for me. Of course you have no responsibility in | the matter at all. It 4s sometling you ‘What a baby at school. -I had hoped it would. 1 gone pang.” He looked up and smiled. “It is too late. I am quite hopeless. “You are quite changed,” she said, “Changed! Thank you.” He laughed unpleasan That is the mildest word any one has used yet. But I've really no right to complain; the strong-, est. things they say are quite true.” “What! all they say? “Well, if the particular stories they have told you are not true, others equally discreditable are, It's the me thing.” She rested her chin on the knuckles ange tone at the last, or | time. their hints that he was repeating him-| “I think.” she said, “he has been and that he was, after all, only |sitting up very late at night, and has a clever plagiarist, and had too reten-|not had sleep enough; he has been tive 2 memo: This had been said of | playing and working too hard, and he} better men 1 he.» But he did mind |has been taking himself too seriously. |; js just antmal pictures. There is what hia friends said, for he believed | Of course,” she added, with the air of|no question of which to chonse oc they could be actuated. only dy |one who wishegto be quite fair, “there | there shouldn't be, for a man like you. his best self, and he wasjare some ings @ man ‘must £0 | that is the admiration of a lot of silly at that time engaged in watching his|through with which we women £0|\,ymen to the friendship of such | best self critically to see how well it | around.” tanding this sudden shock of admiration and easily given sympath: “Confound my Puritan ancestors, anyway!" he said one day to Allce Ingram. “It's all their doing. gave me an artistic temperament and on-bound conscience, and expect © decide which one of them is to win. They won't compromise, said Miss Ingram, rentless t all the blame on your ancestors. Of course you Lave no sp protested, meekl, Good Angel migh' * Miss Ingram answerei and, besides, you get know be They | { | } * I don't like being called | don't, rei And ft only makes it worse to pretend | ike such a horrid sort of|to be any better than I am, and tolyou, Alice.” ym- | cheat h from silly girls, and a/| thinking I axa. married women who ought to|than what he wishes to be at his worst [friends as you have, who care for the |Dest that is in you? How can you tell “Thank you," Thorold sald, grimly “You are .v good, but I have ex- cuses enozy*. J can supply them my- self” Thorold stood up smiling, and shook The girl showed no sign of annoy-|his head. “I tell you it is no use, ance at this, bot still regarded him| Alice.” he sald. “I am honestly not thoughtfully, “The only saying clause | worth it. I've given up, and I'm going I see,” she said; “is your saying you|my own way. All these things you say hoped something might step in to help | have lost thelr meaning. They don't you. Of course,,{f a man wants to be|reach me. It js like some one talking saved from himself he has won half/a language J have. forgotten. You the fight, and he must win the other|needn't think {t didn’t hurt at first half, to No young woman is going | when I saw which way I was going, to do it but it doesn’t hurt now. I like ft, and “The pathetia part of it is," he an- |do it because I like it. and I am not swered, “that I don’t want to be helped |going to pretend I don’t. I am pleas- or to be saved, I said I did, but I| ing myself entirely. Don't look at me I like it better as it {s.|like that. I'm net worth troubling about. I'm not worth a thought from Ho stopped, and added, sharply, “Certainly not tear “I'm not ashamed of my tears, if there are any in my eyes,” myself and my’ friends into A man ts no better ter jmoment. You cannot judge him hy|answered; “but Ir sbould think you This was in Paris. Since then the |what he happens to want to be when| would be. ar world, as far as the world could judge, |he ts worked up to do great things and| “I'm not.” he said, simply. “Think of went very well with Archibald Thor-|inspired by other people. I like to|it—I'm not! That's what I've come to. old; but Miss Ingram, through mutual | waste my time and to has po respon- friends snd from his infrequent let- | stbilitie ters, hat a struggle was going on between the artistic temperament and the Puritan conscience, and she wa v ead as to seemed to her that th the world 3 80 ready to excuse so much in so charming and brilliant a young man for the work ne had done © result. It very fact that made it a more necessary for him to keep himself untarnished from the wortd, nd to refuse to accept its indulgences, because they were 30 easily given. It Was this quality in Alice Theram that attracted Thorold. She had ap- pealed to him when he had first met her, just as she had appealed to many other men, ‘through her cleverness and her remarkable beauty; but what had fascinated him the most. and ‘what had kept him true to h ought, if not in deed, was her u fact that she excused in herself o: others, that she would have no compromt that, ashe protested, she would and Tf Jike dangling in bou-| word you spoke meant— Goirs better than working, and I like| “Stop! don’t!” she sald, breathieasly, the cheap admiration of a lot-of fools|and holding her hands bef her, better than the esteem of a few|"don't! How could you?" |friends; and I can’t, for the life of me,| “That, I should think,” he ‘sald, jany } & quality— | want see why I should live s lie to them and /“would convince you of the truth of myself, and cover up the true badness |all I have said. I can't go muth lower that’s in me. And T am not going to|than that, can I?" He did not look at any long If I cared to be fine and | her again, but turned and left the room strong, {t would be natural enough and | without trying to take her hand or easy to be so; and if I don’t care for|saying good-bye. “ i hat was my last chance. It has failed, and now I can go to the devil with # perfectly clear conscience,” that, it 1s only hypocrisy and waste of time to be anything that Inoks like it. I came here today to fell you this my- self, so that there could be no longer Miss Beatrice er “Trix” . Gwynn., coubt in yout mind, and I don't|who lived next door to Mrs, Taness, want you to waste any more thought jout St. John’s Wood way. posea for or friendship on any one as unworthy |the great artists and all of the fasb- of both as myself, I felt I was de-|ionable photographers. She had two ceiving you, and.I wanted you to knpw./very dear friends, the beautiful Mrs. That's why I came. I never deceivei|Inness ana Captain Cathcart, a very you bi , and I wished you to know—|brave and gcednatured but simple- you to be disgusted with me and |souled gentleman and officer of the a|understand me just as lam, The moan |Inniskilien Dragoons. ou knew is go: “Wi and you—”* “Ican't stop, thanks,” Thorold said. have I to do with it? she|"T just came to see if you and Cath- idly. “You are not answerable cart would come in to supper at my jan after-thought. letters at| But yon cannot keep it up too long. | 004 of you to come. Tell © determined to let yourself to| would serv impatiently; “they fall in love with a|man, jme there Js any question about it—or|ke was already of which to choose? |with what had come to her at second the girl! And yet, there was a time when every | Mra, Inness might prefer st that way. \ “Oh, Mildred won't mind,” said Miss Gwynn, lazily, “She'll come if I ask hes; and then, besides, she's just dotty to“ineet you. She told me, wien I sald 1d met you, that she'd rather—" “Well, that's all right, then.” Thor- old interrupted, hastily. “It's” yery cart to ask for the box as he goes \n.” There were several things Thorold had promised himself {f ho ever let everything go, and now that he had everything go° he wanted to begin with them at onco, and make going back an ‘mpossibflity. Mrs, Tnness was not one of the things he had promised himself, but she Well as another. Her {n a bad atmosphere which does|husband was, or had been. an officer in India, where he had died, or where she hac left bim etili ving; of her acquaintances was particular enough to know or care which. She sat at Thorold’s right at supper, and smiled upon him encouragingly. She was very much pleased with every- thing, and assured him that his chef was as much of a master of his art as his muster was of hi “t and my cook Thorold, gravely. “Mildred always gdes wrong when she tries to be grand,” Miss Gwynn whispered to Cathcart. Just sit still and let them jook, and nat And now she’s telling him her anecdotes of the aristocracy. ‘That's the way she always begins with a new She ‘» siege to him. I don't bother with ‘em, I don't.” +.atheart answered with a heavy bow and a whisper, which caused the youn, model to wave her fork at him pla: fully ana 7 “Oh, you, you don't count.” Mrs. Inneas had tried several moves; openly expressed admiration for his work did not seem to‘answer. Either thank you,” Thorold had had a surfeit of it or Wanted !t more highly spleed, for he aid not seem to heed {t, So she adopted @ politely fashionable tone, and talked of the great people of the hour ahd of their escepades, until she suspected from a light in Thorold’s eyes that intimately familiar hand, and that he knew it had come to her at second hand. So she became herself, and was bold and amusing and daring and familiar. Thorold watched her without attempting to conceal his admiration, not for her, but for her beauty, which was unquestionable. It seemed to him, now that it was writ- ten that he was not to appreciate his f00d angels, he must make the most of his bad angels, and this one was no worse nor no better than the rest, and sho was certainly wonderfully good to look at. “If you are ready,” ho said, ill take the coffee in the other Cathcart sank into one of the big leather chairs with a sigh of content. “Jolly sort of place, thts Thorold,” hé sald. Mrs. Inness poured out some brandy for herself, but Miss Gwynn went back to the dining-room, and returned car- rying the champagne in its bucket, an4 placed it beside her on the floor, “This is Liberty Hall, is it not?” she said. “I fancied eo, your man to have some mote of th.s ready. The captain and I lke it.” When Thorold returned, Mrs, Inness |was at the plano playing the pas du jquatre from the Gatety, ‘and Miss Gwynn was dancing: “I tell her it's a shame she doesn't go on the stage, Thorold.” said Cath- cart. Mrs. Inness rose from the piano in apparent confusion. “I don't know ‘what Mr. Thorold swill think of our taking possession in this way,” she ex- claimed. i “Oh, don't stop,” sala the American. “It's very pretty But the woman refused. She con- fessed to an awe of her host which she could not explain, and which troubled her tn consequence. She could not understand him. ‘Thorold rolled’ up some cf the cugs, leaving a bare place on the floor, and sitting down before the piano, began a no one! said) tell her ta} You'd better. teil, tinctly conscious that he was not hay- ing © good time. He argued that this so because the impressions of the afternoon still hung upon him, and that when they had worn away he would be in a more appreciative mood. “What ® prig I am!” Thorold sai, impatientiy, He decided swiftly that he was much too superior a person, and that i¢ he meant to enjoy his new freedom he must crush the rising pro- tests of past tastes and traditions and give himself tc the present. He came into the room smiling. “Sing us some- thing, Miss Gwynn,” he said. “I wouldn't dare, before you,” she said; and then, to show how little sho meant this, she sat down and ran her fingers over the keys of the plano, “I'll sing xeon something of Ivette Gutll- bert’ she sald. “My French is beast- ly, but I haye to sing “hem in French, so that Cathcart won't’ tinderstand. “Oh, don, Trix,” said Mra. Inness. “They're so low." Thoreld caught himself smiling at this, and to find that Mrs. Inness had her own ideas of propriety. Then he corrected himself mentally for ‘still criticising and posing asa superior b»- ing. He was sick and“disgusted with {t all and with himself. “ The giri at the piano wa, singing with none of Gutl- |bert’s innocence of manner, but was jgsiving each line its full meaning. Mrs. Inness laughed, and looked consciously jat the floor; Cathcart approved doubt- fully, and suggested as a compromise & song from the mustc-halls. “No.” said Miss Gwynn; "T’ve been funny long enough. Let Thorold play something. I want to be audience | now.” “Oh, do, Mr, Thorold,” said Mrs, In- ness, effusively, “Play us a lot of things,” said the “the things you pley to the sey, Thorold,” sald Cathcart, “if you wouldn't mind, I'd lke it awfully Thorold had forgétten himaelf and his audience, if yowa sing that ‘Well of Truth. I'd lke to-hear you do it yourself. I'd like to say I'd heard you.” Every instinct and taste of which Thorold was, possessed was offended and rose in rebellion as they spoke to him. He hated them, and he hat. himself for having brought them to. th'x room. The wickedness of Mayfair and not of Bohemia, he determined, /would be his dissipation in the future. He could at least choose bis associates, as heretofore, and he was not unmind- ful that there were those of his own class a little more wicked than Mrs. Inness, if not so beautiful. “What a child I am!" he exclaimed. | He rett- erated to himself that he had chosen his own way. The best and strongest help for good that had ¢ver came into his life had, s0 he belleved, failed hizo, had ceased to move him that very day; and he thought, in his inexperienc: that what he needed now was to make goimtg back, or the thought of golng back, an impossibility. And then there camo to him an fa- spiration.. In the three months tn which the Puritan conscience nd the artistic temperament had been ‘strug- sling for the mastery he had written and composed the music for a song. The song was the expression of all that had.been going on in his mind; tt meant to him the story of what ho had gone through, and through which he was still going—all that he’ had lost. all his doubts, and regret for what was lost. He had not sung it'to any one. He had even locked the doors when he sang it alone; for it had been written when he was feeling more deeply than he had ever felt before, and he guarded it for that reason, even while his artis- |tie judgment assured him that it was, as A work of art, the strongest thing he had ever written. I+ seemed to him now. that if he could bring himself to sing that song to these psople he would shame the best that was In him and the best that had ever come from him, that he would mock the thing that meant most to him, and that {f he cast it before these swine no other senti- ment or principle or tradition of his Ufe could lay clatm to recognition. He turned impulsively toward his guests, smiling strangely. “I want you to hear a new song-Tve written. It's not w funny song; it's “No; you listen to me,” she sald. Her eyes were brilliant, and she had ceased smiling. “I want to talk to you; I've wanted to know you for a long _ “ a tt will you?” | Why," she said, laughing. uneasily, “I've \tata Gatnoart nn [got a dosen pictures of you tn my “Thorold placed his own clgar care- |house now: I sent to the States for folly on the glass rim of one of the them. Yes, 1 cide afd ['m no more candles beside the music-rack, and, 24 |keen about you than a lot more of he waited, turnea a smiling counte-|other women I know. I've thought {f nance upon his audience, and struck |I could meet a man like you—I mean, the opening chord of his song. The you know,” she explained, “the sort of words could have been sung by efther|man I thought you were—that things & man or @ woman. It tegan by tet!- | would be better, or worse, for it. You ‘what it's about. I'll sing you some } funny ones after I have finished {t.” her chin on th f her han, Ho called it “The Daya That Are Gone.” Seamer eagle ny ee ing of the days of the past, the dars | that were gone; and the accompan' ment suggested the brightness of sun- shine and of running’ streams and rustling leaves, of the “lost Eden of |our innocence” and of sweet content; then it merged suddenly into brave: and more powerful strains as the words spoke of ambitions and hopes and of l great deeds for the life in the future. | Thorold had a very good voice, full of dramatic feeling and power, and every word he sang came to the /i ener's ear bearing its proper emphasis as sharp and sure as the lines of an | actor's soliloquy. He began contemptuousty, but the artist in him made it impossible for him to do ought else but sing the song | well, The music change< to low mutter- ings, and the’ words told of doubts and trouble, and then broke out into passion- ate regret'and agony of spirit. Thorold bad forgotten himself and his audience. The music grew in volume, and filled the room with a great cry of mourn- ing, eerie, awful, and despairing. Hope- of the music and of the words—the| impotent ery for the days that could not come again, the futile regret for the chances that had passed and that had not been taken; then the voice of the singer sank and died away with one low deep cry, as, though despairing of succor or relief, without faith and without hope, and the muste running On ended In a wild crash that sounded like the laughter of those already lost, mocking at those just fallen. The room Was strangely silent. ‘Thoroid reached for his cigar and relit {t at the candle. He puffed it back into a flame ayain, and then, ns no one moved, turned slowly toward jquite right to shove them over. see,” she said, laughing unmirthfully, “you never know just who is counting on you in this worl4—do you? A chap like you has responsibilities; but you're You have a liveller time, I fancy—don't you?—than if you bothered with them,” She stopped and looked down, with her Ups presagd together, and breathing heayily. “ it's hard on the others jome:jmes—on that’sick girl [ was tell- ing yOu about, for instance. I guess if he knew, it would about kill her. And it's hard on ne.” Thorold’s cigar was out, and the candles on elther side of the plano had sunk to their socket, and Were sputtering in wavering, uncerta'n flashes. “That's wint you did for me, the woman went on, bitterly. Her votce chilled Thorold.as it came from above like the failing of cold rain upon his bare head. “I counted on you,” she said. “I used to think that as long as there was one man left who believed in us we weren's so bad, that there was a chance of our getting better or our getting back. I've sung thore. songs of leamness and remorse ware the meaning |¥0U'S, and they sort of comforted me. They made me feel there was some- thing good in me too, and I could have loved the man who made me feel: that, the man who wrote those songs, it I had met him. I could have done any- thing for him—anything. Ta have been—different for him if he had wanted me to, and now—now I can't.” Her voice had risen suddenly, but she lowered it again into a sharp, flerce whisper. “I can't. Now that I've met you I can't. I wish 1d never seen you. I'd rather be a fool, pelieving there was one’man who was difterent—difre- rent from all the rest of you. I hate you!” she whispered; “I hate you! I'd made 80 much of you. I counted on his guests. Cathcart sat just ashe had | ¥0u 0, and you're no better than Cath- last noticed him, leaning forward with the haif-burned match still in his hand. The girl at. his feet was staring up at Thorold with wide-operi eyes, \ylead- cart there—not so good, for he doesn't preach one thing and live another. He doesn't pretend to be any better than he 4s—and you, oh! you—you don't ing and terrified. Her lips were @} (ver- | Want to be as 00d as you are. You've ing. And then as Thorold’ smi}, sho | fooled them all—haven't you? You'y @id the only natural thing had |been very clever, Aren't you pleased ever done in her short, silly, ficial fe, and, turning swiftly, threw herse!t ‘across Cathcart’s knees and burst into a wild torrent of tears Thorold sprang up with an exclama- tion thst was half anger and half apolosy. He turned toward the’ older | bt sie of ae two for some! explan:t- y and then sank back again’ slowly before the piano... Mrs. Inness ‘had not altered her position, but the meaning, languishing smile was gone, and had changed to one of frank, open-eyed amusement. Sh was looking at him as though she had known him for a long time in the peat, but as though he had but Yust then disclosed himself. Her e of him that he himself had noticed earlier in the evening had| hallen from her lke a cloak, and she was smiling at him familiarly and with a@ look of perfect understanding and equality. Thorold turned away his eyes and struck the keys resentfuily. What had this woman to do with him? Mrs. Inness rose leisurely, and swept smiling &cross the room toward him. She leaned one bare elbow on the piano, and placed the hand of the| other arm on her hip with the arm her right hand she held the glass, and with the forefinger of the same han4 she pointed at Thorold. She was not & very tall woman, but she seemed to tower above him as he sat looking up at her, his fingers wandering over the keys. Her attitude was too easy to be have.a touch of menace in it and cf insolence. She nodded her head at him, smiling strangely between half- ‘closed erelids. slowly, and smiling with each word, “you're Archibald Thorold, are you? You're the man who wrote “fhe We! of Truth,’ and the oratorios, and those operas the curates go to see. What a jolly. fraud you are!” She laughed easily, and touched the glass to her Ups, 2nd then pushed it-away from her across the piano. “You're the man who writes the songs tho ilttle girls cry over; all about Love and the Idea!. On, | | know! I've.sung them and cried over them, too. And now here you are, just lke anybody ¢ise—arén't you? Just an| everyday, common, ordinary man.” Thorold pressea heavily on the keys beneath his fingers. Mrs. Tnness," he. said, stiMy, “that I ever posed as being anything else.”. “Perhaps not.” the woman went on. easily. “Perhaps not. Hut why aren't! You different? Why aze you just like | all the other Johnnies?" She restod looked into his with frank, wide-opsh eyes. frankness, and looke} up at her un- easily. = “I don’t think I understand you," he said, with severe politeness. ~ “Oh yes, you do,” she laughed, light- ty. “You know you're not like them, I don't mean your being a swell, but the rest of it." ‘She turned and pointed | her hand toward the corner where | Cathcart sat in the setni-darkness pa ting the girl's curls as-they rested his. knee. sleep, or was pretending to sleep, and} the man was puffing softly on his cigar and looking down at her. “You ‘seo, said Mrs. Inness, “if you're able to make Cathcart look as though he had seen @ ghost, end to send Beatrice Gwynn off into hysterics with remorse, you must be differentfrom-most John- nies. And you've made me cry many atime. And I know a girl a sick gir down in Kent. I used t6 play and sing | your songs to her when I was down jthere, and. she—well!—she thinks | @ gilded saint’ i, will you graceful, and to Thorold {t seemed to} “and you,” she said at last, speaking | And yet Thorold doubted her |. She had sobbed herself io | patien: with {t? Aren't you proud?" Her voice broke with a sob, and she turned switt- ly away and swept out of the room into the hall beyond. Thorold sat quite motionless, jhead was bent, and his ‘fingers std rested on the silent keys, All he had jever sald to himself, or all that others had said to him, had never come to him ag¢had thetwords of this woman, whose name Was “as comic: es the Paris road,” and whom he had despised him- self for admiring, even while he pitied hor. He was sore, bruised, and sick, 9 thuugh he had been pelted with stones and pointed at on a pillo’ Outside, the birds in the Park across the streat were chirping violently, and thi ly sun came stealing between the cracks of the blinds into the smoke-laden room. Thorold rose stiMy and uncertainty, 4s though he had been ‘sitting there a very tong time, and followed her. A tall. white figure, muffed and un- recognizable, confronted him in the gray helf-lght of the hall. “Well? she said. ‘ThorolA went to the door and threw it open, letting in the sunlight, and giv- His akirhbo and her head thrown back. In jing them a strangely foreign and un- famillar abr. It was as ifthe night just over were far back in the past. “Mrs, Inness," he said. “you won't understand me, I am afraid. But I want you to know that, thought I have disappointed you, you have helped me |& great deal. I think I owe it to you to tell you this. We never know, as you say; how much we depend on others, ang we can never ‘tell from What source that help we most- need wil) come. % { don't understand” the woman’ said. “Neyer mind," ‘Thorold answered, gently. “Jt is something that you have helped another, is it not?” Cathcart and the girl came into the hall, and Cathcart stepped into the strpet and beckoned to the line of han- soms drawn up by the railings under the overhanging branches of the Park, “I'm sorry T.made such an ass-of my- elf, Thorold,” the soldier said, “but that.song of yours was a bit creepy, now, wasn't it? |. “Rke model stretched a slim white |hand,out from the mass of swan't- |@own, and as Thorola took it in his “I do not Grad (ehidig she stooped and kiesed his hand, And then ran down the steps, laughing, to where Cathcart stood waiting be- side the hansom. Thorold helped Mrs. Inness into the next, and gave her number to the driver. but she called to him to walt. ,She pushed the doors away and leaned forward, “You are angry with me,” she sald, ler eves were wet and pleading. “Yoa |will never forgive. me: id ‘don't know why T spoke as I did. I was a fooi—b cause I don’t want you to hate me. | [W§nt you to forgive tne, and come to see me, inspite of all ¥ sa{d.” “There is nothing to Yorgive, Mrs. Innes,” Thorold answered, carnestly. “I tell you, you have done me a great service. You, have helped me very I know." she interrupted, tm- v. “Yow say that. ut you are angry. Don’t think of what I said. Forget jt and forgive me, and come and see me. Thorold smiled. He could not-help st, for the way seemed to clear now. “Iam very sorry,” he said, “but really I can’t. Yow see, I'm leaving town: “I sail for America thi? morning with some friends from Southampton.” Thorold turned slowly ana Walked back soberly {nto the darkened rooms, He surveyed the room curiously, and for the last time. And it wes here,” he said, gravely, “that I entertained an Thorold said. lancel usawaren” Sat LE iy fan SW a> Yes ee TZ z > YX WAY Kiet SS < SSS =