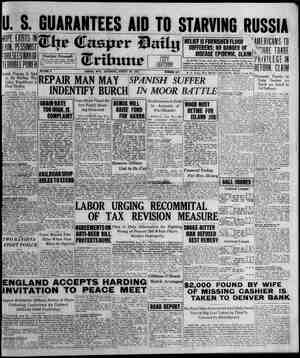

Casper Daily Tribune Newspaper, August 20, 1921, Page 8

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

V — rt SZ ac7Zz es ZT ? we, S zal) \} OUTSIDE - THE « PRISON By RICHARD HARDING DAVIS T was about ten o'clock on the night before Christmas, and very cold. Christmas Eve is @ very-much-oc- | cupled evening everywhere, in a news- paper office especially so, and ali of the twenty odd reporters were out that night on assignments, and Conway ant Bronson were the only two remaining in the local room, They were the very best OMriends, in the office and out of it; but am the city editor had given Conway the Christmas Eve story to write insteaq of Bronson, the tatter , and thelr relations were strained. I use the word “story” in the Newspaper sense, where everything written for the paper is = story, whether tt th an obituary, or a reading | notice, or a dramatic criticism, or a) Gescriptive account of the crowded streets and the ilghted shop windows of @ Christme: Eve Conway hed fin- ished his story quite half an hour be- fore, and should have sent {t out to be mutilated by the blue pencil of a copy editor; but as the city editor had twice appeared at the deor of the local room, as though looking for some one to senda out on another assignment, both Conway and Bronson kept on steadily writing against time, to keep him off until some one els6 came in. Conway had written his concluding ih a dozen times, and Bronson had con- ecientiously polished and repolished a| three-line “personal” he was writing. | concerning a gentleman unknown to| fame, and who would remain unknown to fame until that paragraph appeared in print The city editor blocked the door for hird time ‘and looked a> @gapson with «a faint smile feptical appre- ciation. “Is that very portant?” he asked Bronson said, “ doubtfulty, as though he did not thina his opinion should be trusted on such a matter, and eyed raph with critical inter- | est. rushed his pencil over} his paper, with the tip of his tongue| showing between his teeth, and became | suddenly absorbed, “Well, then. if you are not very busy,” said the city editor, “I wish you would g0 down to Moyamensing. They Conway release thut bank-robber Quinn to- night, and it ought to make a good story. He was sentenced for six years, I think, but he has been commuted for good conduct and bad health. There was a preliminary,story about it in the paper this morning, and you can 11 the facts from that. It's Christmas and all that sort of thing, and-you ought to be able to make something of ‘There are certain stories written for ® Philadelphia newspaper that circle into print with the regularity of the seasons. There is the “First Sunday in the Park," for example, which comes on the first warm Sunday in the spring, end which is made up of a talk with a park policeman who guesses at the number of people who have passed through the gates that day, and an nouncements of the re-painting of the boat-houses and the near approach of the open-air concerts. You end this story with an allusion to the presence in the park of the “wan-faced children of the tenement,” and the worthy work- ingmen (if it 1s a one-cent paper which the workingmen are likely to read),| and tell how they worshipped nature in | the open air, instead of,saying that in place of going properly to church, they sat around in thelr shirt-sleeves and scattered egg-shells and empty beer bottles and greasy Sunday newspapers over the green grass for which the worthy men who do not work pay taxes, Then there is the “Hottest Sun- day in the Park,” which comes up a month later, when you increase the Park policeman’s former gu teen thousand, and give ite by adding a list of the small boys drowned in bathing. The “First Haul of Shad” in the Delaware is another reliable story, as/ is also the first ice fit for skating in| the park and then there {s always the| Thankegiving story, when you ask the theatrical managers what they have to| be thankful for, an? have them tell you, “For the best season that this the- | atre has ever known, sir.” and =ffer you! & pass for two; and there,is the New| Years story, when you interview the! local celebrities as to what they most) want for the new year, and turn their commonplace replies into’ something clever. There is also a story on Christ- mas Day, and the one Conway had jus: written on the stret scenes of Christ- mas Eve, After you have written one of these stories two or three times, you find it just as easy to write it in the office as anywhere else. Ona gentle- man of my acquaintance did this most unsuccessfully. He wrote his Christ- story with the aid of a direc- tory and the file of a last year’s paper. From the year-old file he obtained the names of all the charitable institutfons which made a practice of giving their charges presents and Christmas trees, and from the directory he drew the names of their presidents and boards ef directors, but ashe was unfortu- nately lacking in religious knowledge and a sense of humor, he included all the Jewish institutions on the list, and they wrote to the paper and rather ob- jected to being represented as decorat- ing Christmas trees, or in eny way celebrating that particular day. But of all stale, flat, and unprofitable stories, this releasing of prisoners from Mor- amensing was the worst. It seemed to Bronson that they were always re- leasing prisoners; he wondered how they possibly left themselves enough to make a county prison worth while. And the city editor for some reason always chose him to go down and see them come out As th2y were released at midnight, and ever did anything of moment when they were released but to immediately cross over to the near- est saloon with all thelr disreputable | friends who had gathered to meet them, it was trying to one whose re- gard for the truth was at first un-! jtimes you'd | dying gladiator.” | leave the cab at Fifteenth Street, near | but the man only gathered up his reins } shaken, and whose imagination at the | Moyamensing Prison for the robbery | last became exhausted. So, when Bron- son heard he to release another prisoner in puthetic descriptive prose. he lost heart and patience, and re- belied. “Andy,” he said, sadly and tmp | sively, “if I have written that story | once, I have written it twenty times. I have descrsed Moyamensing with the moonlight falling on {ts wall Thave described it with the walls shin= ing in the rain; I have described it covered with the pure white snow that falls on the just as weil as on the criminal; and I have made the blood- hounds tn the jail-yard how! dismally —and there are no bloodhounds, as you very well know; and I have made re- leased convicts declare—thetr intention | to lead a better and ® purer life, when they only said, ‘If youse put anything in the paper about me I'll lay for you and I have made them fall on the neck: of thelr weeping wives, when they only asked, ‘Did you bring me some to- bacco? I'm sick for a pipe’; and I will not write any more about it; and if I| do, I will do it here in the office, and that is all there Is to it” “Oh yes, I think you will” said the/ city editor, easily, “Let some one else do it,” Bronson pleaded—"“some one who hasn't done the thing to death, who will get a new Point of yiew—" Conway, who had’ stopped writing. and had been grinning | a@t Bronson over the city editor's back, Stew Buddenly grave and xbsorbed, and began to write again with feverish in- dustry, “Conway, now, he's great st| that sort of thing. He's ‘The city editor lata a clipping from the morning paper on the desk, and took @ roll of bills from his pock “There's the prelimmary. story,” Le| said. “Corway wrote it and it moved | several good people to stop at the bus!- ness office on their way downtown and leave something for the released con- vict’s Christmas dinner. The story a very good story, and impressed them, he went on, counting out the bills “ns he spoke, “to the extent of fifty-five dollars. You take that and give it to him, and tell him to forget the past, And keep to the narrow road, and leave Jointed Jimmies alone. That money will give you an excuse for talking to him, and he may say something grateful to the paper, and comment on {ts enter- | prise. Come, now, get up. I've spoiled You two boys, You've been sulking i:!] the evening because Conway got that story, and now you are sulking because you have got a better one. Think of it | —setting out of prison after four years, and on Christmas Eve! It's.a beauti- ful story just as it is. But," he added. grimly, “You'll try to improve on 1 and grow maudlin. I believe some- turn a red lght on the The conscientiously industrious Con- way, now that his fear of being sent out again was at rest, laughed at this with conciliatory mirth, and Bronson smiled sheepishly, ang psace was re-| stored between them. | But as Bronson capitulated, he tried | to make conditions. “Can I take a| cab?" he asked. The city editor looked at his watch. “Yos," he said; “you'd better; it's late, and we go to press early tonight, re- member.” “And can I send my stuff down by the driver and+go home?". Bronson went on. “I can write it up there, and our hous I don't want to come ull the way downtown again.” “No,” said the chief; “the driver might lose it, or get drunk. or some- ching.” % “Then can I take Gallegher with ine to bring it back?" asked Bronson. Gal- legher was one of the office boys, ‘The city editor stared at him grimly. “Wouldn't you like a typewriter, aid Conway to write the story for you, and a hot supper sent after you?" he asked. ay Gallegher will do,” Bronson Gallegher had his overcoat on and a nighthawk at the door when Bronson came’ down the stairs and stopped Ught a cigar in the hallway. “Go to Moyamensing,” said Gallegher to the driver, , Gallegher looked at the man to sce if he would show himself sufficiently human to express surprise at their visiting such @ place on such a night, to impassively, and Gallegher stepped into the cab with a feeling of disap- pointment at having missed a point. He rubbed the frosted panes and looked out with boyish interest at the passing holiday-makers. The pave- ments were full of them and their bun- dies, and the street as well, with waver- ing Unes of medical students and clerks blowing joyfully on the horns, and pushing through the crowa with onc hand on the shoulder of the man in front. The Christmas greens hung in long lines, and only stopped where a street crossed, and the shop fronts were so briiliant that the street Was as light as day. It was so light that Bronson coud read the ‘clipping the city editor had given him. “What is it we are going on?” asked Gallegher, Gallegher enjoyed many privileges: they were given him. principally, 1 think, ‘because if they had hot been siven him he would have taken them. He was very young and small, but sturdily built, and he had a general knowledge which was entertaining, ex- cept when he happened to know more about anything than you did, It was impossible to force him to respect your years, for he knew all about you, from the number of lines that had been cut off your iast story to the amount of your very small salary; and there was ah awful simplicity about him, and a certain sympathy, or it may haye been merely curfosity, which showed itself towards every one with whom he came in contact. So when he asked Bron- son what he was going to do, Bronson read the clipping in his hand #ioud. of the Second National Bank at T; cony, will be liberated tonight. His sentence has been commuted, owing to good conduct and to the fact that for the last year he has been in very Ml health. Quinn was night watch- man the Tacony bank at the time of the robbery, and, as was shown at the trial, was in reality merely the tool of the robbers. . He confessed to complicity in the robbery, but dis- claimed having any knowledge of the later whereabouts of the money, which has never been recovered. This was his first offense, and he had, up to the time of the robbery, borne a very excellent reputation. Although had been a most unhappy one, his friends claiming ‘that his wife and her mother were the most to blame. | Quinn took to spending his evenings | away from home, and saw a great deal of a young woman who was sup- posed to have been the direct cause of his dishonesty. He admitted, in fact, that it was to get money to en- able him to leave the country with her that he agreed to assist the bank- receipt of ten dollars from M. J. to be given to Quinn on his relea: also two dollars from Cash and three c. one of disdain. he said, ‘Is there? done time once, letting him out. and they're Now, if it was Kid McCoy, or Billy Porter, or some one like that—eh?" Gallegher had as high a regard for a string of aliases double line of K.C, B. and a man who ha once was not worthy of his considera- tion. ‘And you will work in those bloodhounds again, too, I suppose,” he said, gloomily. The reporter pretended not to hear this, and to doze in the corner, and Gallegher whistled softly to himself and twisted luxuriously on the cush- ions. It was a half-hour later when Bronson awoke to find he had dozed in all seriousness, as a sudden cur- rent of cold air cut in his face, and he saw Gallegher standing with his hand on the open door, with the gray wall of the prison rising behind him. Moyamensing looks like a prison. It is solidly, awfully suggestive of the sternness of its duty and of the hope- lessness of its failing in it. It stands [like a great fortress of the Middle Ages in a quadrangle of cheap brick and white dwelling-houses, and a few mean shops and tawdry saloons. It has the towers of a fortress, the pil- lars of an Egyptian temple; but more impressive than either of these is the promising wall that shuts out the prying eyes of the world and encloses those who are no'longer of the world. It is hard to imagine what effect it has on those who remain in the |houses about it. One would think they would sooner live overlooking a graveyard than such a place, with its mystery and hopelessness and unend- ing silence, its hundreds of human inmates whom no one.can see or hear, but who, one feels, are there, Bronson, as he looked up at the prison, familiar as it was to him, ad- mitted that he felt all this, by a frown, ‘Youare to wait here un- Bronson read, ‘who was sentenced to six years in| til twelve,” he said to the driver of the nighthawk. “Don’t go far away.” but lately married, his married life) |and Bronson wondered, if they drac’ robbers. The paper acknowledges the |they must follow one another to the comment on this was/back later to say that it was growing “There isn't much in |colder, and that he had found the Just a maa driver in a saloon, but that he was, after a name as others have for a|the comment that one “might Gallegher assented listlessly, with well nd C. S. L.'s, | be eatin’ as doin’ nothin’. He went awful simplicity of the bare, uncom-| jof anticipati jlocked at him doubtfully. Bronson and the boy walked to an oyster-saloon that made one of the line of houses facing the gates of the prison on the opposite side of the street, and created themselves at one of the tables from which Bronson could see out towards the narthern entrance of the jail. He told Gal- legher to eat something, so that th saloon-keeper would make them wel come and allow them to remain, and Gallegher climbed up on a high chair, and heard the man shout back his} order to the kitchen with a faint smile It was eleven o'clock, but it was even then necessary to begin to watch, as there was a tradi- tion in the office that prisoners with influence were sometimes released before their sentence was quite ful- filled, and Bronson eyes the “released prisoners’ gate” from across the top| of his paper. The electric lights be- fore the prison showed every stone in its wall, and turned the icy_pave- ments into black mirrors of light. On a church steeple a block away a round clock-face told the minutes, | ged so slowly to him, how tardily men in the prison, who could not see the clock’s face. The office-boy fin- ished his supper, and went out to explore the neighborhood, and came to all appearances, still sober. Bron- son suggested that he had better sac- rifice him once again and eat some- thing for the good of the house, and offended but|outeagain restlessly, and was gone for a quarter of an hour, and Bron- son had Ye-read the day’s paper and the signs on the wall and the clipping he had read before, and was thinking of going out to find him when Galle- gher put his head and arm through the door and beckoned to him from the outside. Bronson wrapped his coat up around his throat and fol-| lowed him leisurely to the street. Gallegher halted at the curb, and pointed across to the figure of a woman pacing up and down in the glare of the electric lights, and mak- ing a conspicuous shadow on the white surface of the snow. “That lady,” said Gallegher, ‘asked me what door they let the released prisoners out of, an’ I said I didn’t know, but that I knew a young fellow who did.” Bronson stood considering the pos- sible value of this for a moment, and then crossed the street slowly. The woman looked up sharply as he ap- proached, but stood ‘still. “If you are waiting to see Quinn,” Bronson id, abruptly, “he will come out of that upper gate, the green one with the iron spikes over it.” The woman stood motionless, and She was quite young and pretty, but her face was drawn and wearied looking, as though she were a convalescent or one who was in trouble. She was of the working class. “Iam waiting for him myself,’’ Bronson said, to reassure her: “Are you?" the girl answered vaguely. "“Did you try to see him?” She did not wait for an answer, but went on nervously: “They wouldn’t let_me see him. I have been here since noon. I thought maybe he might get out before that, and I’d So {might as well give him this, too, be too late. You are sure that is the| gate, are you? Some of them told me there was another, and I was afraid I'd miss him. I've waited so long,” she added. Then she asked, “You're a friend of his, ain't you?” “Yes, I suppose so,” Bronson said. | “I am waiting to give him some; money.” “Yes? I have some money, teo,’ the girl said, slowly. “Not much. Then she looked at Bronson eagerly | and with a touch of suspicion, and) took a.step backward. “You no| friend of hern, are you?” she asked | | sharply. “Her? Whom do you mean?” asked Bronson. But Gallegher interrupted him. ‘Certainly not,” he said. “Of course not.” . The girl gave a satisfied nod, and) then turned to retrace her steps over! the beat she had laid out for herself.) “Whom do you think she means?” Bronson said fn a whisper. “His wife, I suppose,” Gallegher answered, tmpatiently. The girl came back, as if finding} some comfort in their presence. “She's inside now,” with a nod of her head towards the prison. “Her and her mother. They came in a cab,""| she added, as if that circumstance made it a little harder to bear. ‘And when I asked if I could see him, the man at the gate said he had orders not. I suppose she gave him them orders. Don't you think so?’ She} did not wait for a reply, but went on| as though she had been watching alone for so long that it was a relief to speak to some one. “How much money have you got?” she asked. Bronson told her. “Filty-fi dollars!” “Was It You That—Did You Send Any Money to a Paper?" Asked Bron son laughed, sadly. “I only got fifteen dollars. That ain’t much, is? That’s all I could make—I've been sick- that and the fifteen I sent to the paper.” “Wes it you that—did you send any money to a paper?” asked Bron- son: “Yes; I sent fifteen dollars. I thought maybe I wouldn't get to speak to him if she came out with him, and I wanted him to have the money, so I sent it to the paper, and asked them to see he got it. I gave it under three names: I give my initials, and ‘Cash,’ and just my name—‘Mary.’ I wanted him to know it was me give it. I suppose they'll send it all right. Fifteen do!- lars don't look like much - against fifty-five dollars, does it?’ She took small roll of bills from her pocket and smiled down at them. Her hands were bare and Bronson saw that they were chapped and rough. She rubbed them one over the other, and smiled at him wearily. Bronson could not place her in the story he was about to write; it was a new and unlooked for element, and one that promised to be of moment. He took the roll of bills’ from his | pocket and-handed them to her. “You; said. “I will be here until he comes| out, and it makes no difference who! gives him the money, so long as he! gets it.” The girl smiled confusedly. The! show of confidence seemed to please| her. But she said, “No, I'd rather | not. You see, it isn’t mine, and I did work for this,” holding out her own roll of-money. -She looked up at him steadily, and paused for a moment, and then said, almost de- The gir! flantly, “Do you know who I am?” “I can guess,” Bronson said. “Yes, I euppose you can," the girl answered. ‘Well, you can believe it or not, just es you please’’—as though he had accused her of som; thing—"but, before God, it wasn my doings.” She pointed with a wave of her hand towards the prison wall. “I did not know it was for me he helped them get the money until he said so on the stand. I didn’t know he was thinking of running off with me at all. I guess I’d have gone if he had asked me. But I didn’t put him up to it as they said I'd done. I knew he cared for me a lot, but I didn’t think he cared as much as cr ———————— and with the light of « Dig lantern shining down on them. They could not see the clock-face from where they stood, and when Bronson :ook out his watch and looked at ft, the girl turned her face to his appeal- ingly, but did not speak. “It will be only a little while now,” he sald. gently. He thought he had never seen so much trouble and fear and anxiety in so young a face, and he moved towards her and in a whisper, as though those ide could hear him, “Contra! yourself if | you can,” and then added, doubttully, \and still in a whisper, “You can take my arm if you need it.” The girl shook her head dumb}y, but took a that. His wife—. she stopped, and seemed to consider her words care- fully, ag if be quite fair in what she said- is wife, J guess, didn't Rnow just how to treat him. She was too fond of going out, and hav- ing company at the house, when he was away nights watching at the bank. When they was first married she used to go down to the bank and sit up with him to keep him com- pany; but it was lonesome there in the dark, and sho give it up. She was always fond of company and hav- ing men around. Her and her mother are a good dea! alike. Henry used to grumble about it, and then she'd get mad, and that’s how it begun. And then the neighbors talked, too. It was after that that he get to com- ing to see me. I was Iiving out in service then, and he used to stop in to see me on his way back from the bank, about seven in the morning. when I was up in the kitchen getting breakfast. I'd give him a cup of cof- fee or something, and that’s how we got acquainted."’ ‘ She turned her face away, and looked at the lights farther down the street. “They scid a good deal about me and him that wasn’t true.”” There Was a pause, and then she looked at Bronson again. “I told him he ought |to stop coming to see n@ and to he liked me best. TI couldn't help his saying that, could I, if he did? Then he-——then this come,” she nodded to the jail, “ | They said that I stood in with the | bank-robbers, and was working with them; they said they used me for to |get him to help them.” her face to the boy and the man, and they saw that her eyes were wet and that her face was quivering: ‘That's likely, isn't it?’ she demanded, with asob. She stood for a moment look- ing at the great fron gate. and ther at the clock-face glowing dully through the falling snow: it showed a quarter to twelve. “When he was |put away,” she went on, sadly, ‘I started in to wait for him, and out. I only got three dollars a week and my keep, but I had saved one hundred and thirty dollars up to last April, and then I took sick, and it all went to the doctor and for medicines. |1 didn’t want to spend it that way, but I couldn’t.die and not see him. Sometimes I thought it would be bet- ter if I did die and save the money any more trouble, anyway. But I |couldn’t make up my mind to do it. ;! did go without taking medicines jbut I had. to live—T just had’ to. pSometimes I think T’ pught to have given up, and not tried to get well. What do you think?” Bronson shook his head, cleared his throat as if he were going to speak, but said nothing. Galle- gher was looking up at the girl with large, open eyes. Bronson wondered if any woman would ever love him $8 much as that, or if he would ever love any woman so. lonesome, and he shook his “head. |‘“Well?" he said, impatiently. |. “Well, that’s all; that’s how it is,” jshe said. ‘‘She’s been living on there and \seeing a5 many men as before, and |kept getting pitied all the time; | everybody was so sorry for her. When | he was so bad that time a year ago with his lungs, they said in Facony that if he died she'd marry Charley Oakes, the conductor. He's always going to see her. her knew me, and I got word about how Henry was getting on. couldn’t see him, because she told lies about me to the warden, and they wouldn’t let me. But I got word about him. He's been fearful sick just lately. He caught a cold walk- ing in.the yard, and it got down to his lungs. That's why they are let- ting him out. They say he’s changed so. I wonder if I'm changed much? T've fallen off since I was ill.” She passed her hands slowly over her face, with a touch of vanity that hurt Bronson somehow, and he wished he might tell her how pretty she still was. “Do you think he'll know me?” she asked. “Do you think she'll let me speak to him?” “I don’t know. How can I tell?” said the reporter, sharply. He was strangely nervous and upset. He could see no way out of it. The girl seemed to be telling the truth, and yet the man’s wife was with him and by his side, as she should be, ‘and this woman had no place on the scene, and could mean nothing but trouble to herself and to every one else. “Come,” he said, abruptly, “we had better be getting up there. It’s only five minutes of twelve.” The girl turned with a quick start, and walked on ahead of them up the drive leading between the snow-cov- |ered grass-plots that stretched frgm the pavement to the wall of \the prison. She moved unsteadily and slowly, and Bronson saw that she was shivering, either from excitement or the cold. “T guess, said Gallegher, m an “that there’s going to awed whispe | make it up with his wife, but he said) nd they blamed me for it.) She lifted | to} save something against his coming} for him, and then there wouldn't be) they laid out for me for three days; | It made’ him feel; (at Tacony with her mother. She kept! Them that knew| std Hiagesn: | gaid, confusedly, They stopped a few yards before| the great green double gate, with a\ smaller door cut in one of its hulves. | step nearer him, as if for protection, and turned her eyes fearfully towar: jthe gate. The minutes passed on slowly but with intense significance, |and they stood so still that they could hear the wind playing through the wires of the electric Light back of them, and the elicking of the icicles tas they dropped from the edge of the prison wall to the stones at their feet, And then slowly and laboriously, | and like a knell, the great gong of the |prison sounded the first stroke of twelve; but before it had counted |three there came suddenly from all. the city about them a great chorus of clanging bells and the shrieka and |tooting of whistles and the booming of cannon, From far down town the big bell of the State-house, with its | prestige and historic dignity back of it, tried to give the time, but the other bells raced past it, and beat out jon the cold crisp air joyously and | Uproariously from Kensington to the |Schuylkill; and from far across the | Neck, over the marshes and frozen |ponds, came the dull roar of the guns at the navy-yard, and from t! | Delaware the horse tootings of t) }ferry-boats, and the shrieks of the jtugs, until the heavens seemed to |rock and swing with the great wel- come. | _Gallegher looked up quickly with a queer, awed smile. | “It's Christmas,”’ he said, and then he nodded doubtfully towards Bron. son and said, ‘Merry Christmas, si: It had come to the waiting holiday crowd down-town around the State- house, to the captain of the tug fog- bound on the river, to the engineer | sweeping across the white flelds and sounding his welcome with his hand on the bell-cord, to the prisonets be- yond the walls, and to the children all over the land, watching their stockings at the foot of their bods. | And then the three were instantly ;drawn down to earth again by the |near, sharp click of opening bolts and locks, and the green gates swung heavily in before them. The jail-yard was light with whitewash, and two great lamps in front of round refles- tors shoné with bliading force in their faces, and made them start sud- denly backward, as though they had heen caught in the act and held in the circle of a policeman’s lantern. In the middle of the yard was the carriage in which the’ prisoner's wife and her mother had come, and | around It stood the wardens: and turnkeys in thelr blue and gold uni- \forms. They saw them dimly from jbehind the glare of the carriage lamps that shone in their faces, and Saw the horses moving . slowly | towards them, and the driver holding |up their heads as they slipped and ) Slid on the icy stones. The_girl put her hand on LGronson’s arm and |clinched it with her fingers, but her eyes were on the advancing carriage. The horses slipped nearer to them and passed them, and the lights from th2 lamps now showed thein backs and the paving-stones beyond them, and left the cab in partial darkness. It was a four-seated carriage with a | movable top, opening into two halves jat the centre. It had been closed when the cab first entered the prison, a few hours before, but now its top was thrown back, and they could see that it held the two women, who sat facing each other on the farther side, and on the side néarer them, stretch- ing from the forward seat to the top |of the back, was a plain board coffin, | Prison-made and painted black. The girl at Bronson’s side gaye head between his shonlders as though some one had struck at him from above. Even the horses shied with jSudden panic towards one another, |and the driver pulled them in with an | oath of consternation. and threw him- {self forward to look ‘beneath their |hoofs, And as the carriage stopped the girl sprang in between the wheels and threw her arms across the lid of the. coffin, and laid her face down upon the boards that were already damp with the falling snow. “Henry! Weary! Henry!” moaned! é The surgeon who attended the |prisoner through the sickness that had cheated the country of three hours of his sentence ran out’ from the hurrying crowd of wardens and drew the girl slowly and gently away, and the two women moved on triumphantly with their sorry victory. she |, Bronson gave his copy to Gallegher to take to the office, and Gallegher laid it and the roll of money on the city editor's desk, and then, so the chief related afterwards, moved off quickly to the door. The chief looked |up frcm his proofs and touched the roll of money with his pencil. Here! What's thist’ he asked. “Wouldn't he take it?’ Gallegher stopped and straightened himself 2s though about to tell with proper dramatic effect the story of the night's adventure, and then, as | though the awe of it still hung upon him, backed slowly to the door, and 0, sir; he was— he didn't need it.” Copyright, 1921, by The Wheeler Sundicata. Ina | something between a cry-and a shriek. I! that turned him sick for an instant, and that made the office-boy drop his. > A 2] ran pes KL SEN ez SSS aN Yamane oo es SMZIZEY Y s DSS SEZ ~ Co Sow: IS) Sy ® ~~ ed Atsts <— U; } pez?) ra Lo <x (x Sy NS y ba s 4 AS Pc ng XX Le m SS es zh Z SS = tS