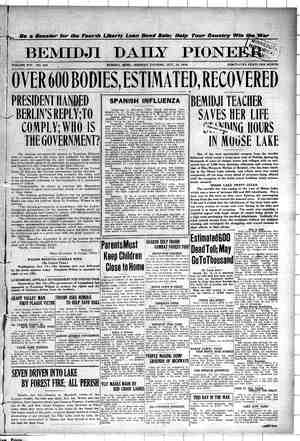

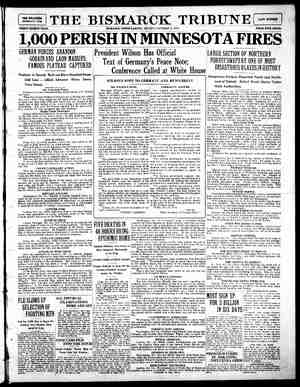

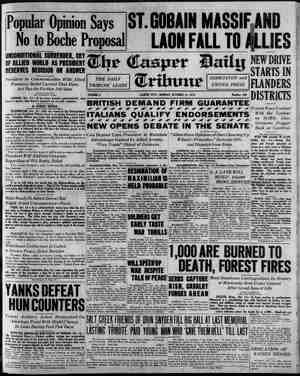

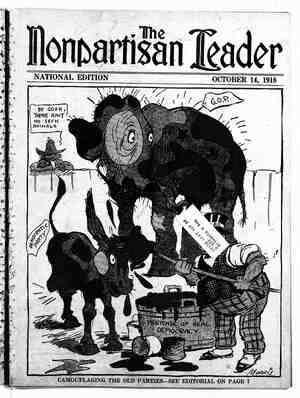

Casper Daily Tribune Newspaper, October 14, 1918, Page 6

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

p—- Albert N. Dep EX-GUNNER AND CHIEF PET i ~ _ MEMBER. OF THE FOREIGN LEGION OF FRANCE CAPTAIN GUN TURRET, FRENCH BATTLESHIP OFFICER NAVY, CASSARD : OF THE CROIX DE GUERRE Cee (18 ty Rady act Benen Co. Through Spal Aranqemers Wi he Gesrge Mae Adara Sav, SYNOPSIS. HAPTER I—Albert N. Depew, author the story, enliste in the United States ~ og four years and attaining 2 of chief petty officer, first-class Til—The great after he is honorably m the navy and-he nh @ determinat war starts discharged for France tion to enlist, ety eee era is 0 the it asard where his matksmanship ‘wins a high honors. HAPTER IV—De: is detached from ship and sent with @ regiment of the gion to Flanders where he soon aself in the front line trenches. ery and makes the acquaisascern? tis an es 1e int ice Of 1 *s*, the wonderful French guns that ve Saved the day for the allies on many ordered back to his vogimens ithe oO rey nt eo nt line trenches. HAPTER VI—Depew ce snd. se his first goes “over th German in a bay- HAPTER VII—His company takes part azother raid on the German trenches 1 ghortly afterward assists in stopping fierce c! of the Huns, who are down as they cross Ni x lo ‘s Fo Sy Moe ey ey 5 w is Dut scapes unhurt. Trent HAPTER IX—He is shot through the eh in a brush with the Germans and sent to a hospital, where he quickly X—Ordered back to sea duty, pew ins the Cassard, which makes eral Dardanelles as a con- PR aoeard ip aicaper n imost Gen by the Turkish batteri many hot engagement je memor= le Gallipoll ‘campaign. Ee battered to jes. ‘HAPTER XII—Depew is a member of landing party which sees fierce he: the trenches at Gallipoli. pea ‘HAPTER XIII—After an unsuccessful an raid, Depew. tries to rescue two ” men in No Man’s Land, but both » before he can reach the trenches, b XIV—Depew wins the Croix Guerre for bravery in passing through terrific artillery fire to summon aid to 3 comrades in an advanced post. 2HAPTER XV—On his twelfth trip to @ Dardanelles, he 1s wounded in a naval mt and, after recovering in a Spital at Brest, ho is discharged from rvice.and sails for New York on the samer Georgic. CHAPTER XXI. A Visit From Mr. Gerard. Late that night we arrived at Dul- en, Westphalia, We were rousted at of the carriages, mustered on the atform, counted, then drilled through 1e streets. In spite of the lateness, 1@ streets were pretty well filled with 2ople; and they zig-zagged us through 1 the streets they could, so that all “1e people would have a chance to see _ te erazy men, as they called us. Most * the people were women, and as soon 3 they saw us coming, they began nging the “Watch on the Rhine” or ome other German song, and it was imny to see windows opening and fat ‘aus, with night-caps on, sticking 1eir heads out of the windows. They ould give us a quick once-over, and ipe up like a boatswain: “Schwein- und—Vaterland—Wacht am Rhein” -all kinds of things and all mixed up. So we gave them “Tipperary” and Pack Up Your Troubles,” and aowed them how to sing. Our guards ad no ear for music and tried to stop s, but though they knocked several 1en dowa, we did not stop until we ad finished the song. Then, after we ad admitted to each other that we ere not downhearted, we shut up. We' would have done so, anyway, be- ause’by this time we were on the out- «irts of the town, and we needed all 1e breath we hag The road we were nm was just one long sheet of ice, and ve could hardly walk more than four teps without slipping and falling. My hoes had wooden soles, and it was ast one bang after another, with the se and myself trying to see which ould hit the hardest. Every time we ell—smash! came a rifle over the ack. I was getting pretty tired, so I said 9 some of the fellows that I was go- ag to sit down and rest, and they said hey would also, So we dropped out nd waited until the guards behind | Ydid not pa I heard, “Any Americans there?” and | I yelled back, “Yes, where are you?" | “Barracks 6-B, Grappe 3.” “Where from?” I yelled. “Boston. Where're you from?” “The U. S. A. and Atlantic ports. See you later.” So, the next morning, I went over to nis barracks and asked for the Yank. They pointed him out to me, where he was lying on the floor. I went over and laid down with him, and we had quite a talk. I will not give his name | here for certain reasons, He had received several wounds at the time he was taken prisoner. He had been in the Canadian service for two years. We used to talk about New York and Boston and the differ- ent places we knew in both towns, and we also talked a lot about the rotten treatment we were receiving, and tried to cook up some plan of escape. But every one we could think of had been used by some one else, and either had failed, or the Huns had fixed it so the plan could not be tried again. We doped out some pretty wild schemes at that. Altogether, we became great pals, and were together as much as possible at Dulmen. The day I left the camp, he gave me a ring made from a shell, and told me to get it safely back to the States, but some one stole it at Brandenburg. One day while I was in his barracks an Englishman stepped out of the door for some reason or other, and though he did not say a word to Fritz, in two minutes he was dead, in cold blood. We never knew why they killed him. At Swinemunde and Neustrelitz, I must admit that the Germans had us pretty badly buffaloed, but at Dulmen the prisoners were entirely different. Dulmen was the receiving camp for the whole western front, and the pris- oners there got to be pretty tough eges, as far as Fritz was concerned, before they had been in camp many days. They thought nothing of pick- ing a fight with a sentry and giving him a good battle, even though he was | armed with rifle and bayonet. We | Soon learned that unless his pals are around a German will not stand by his ‘arguments with his fists. In other words, if he can outtalk you, he will beat you up, but if he cannot, it isa case of “Here comes Heinie going back.” The Russian prisoners at Dulmen were certainly a miserable looking bunch. They spent most of their time wandering around the Russian bar- racks, hunting for rotten potato peel- ings and other garbage, which they would eat. When they saw Fritz throw out his swill, they would dive right through the barbed wire one after another, and their hands and face and clothes were always torn from it. It was unhealthy to stand between the Russians and their garb- age prey—they were so speedy that nothing stopped them. One morning, just after barley-cof- fee time, I came out of the barracks and saw an Australian arguing with the sentry. I was not only curious, but anxious to be a good citizen, as they say, so I went up and slung an ear at them, The Australian had asked Fritz what had been done with the flag that the Huns were going to fly from the Eiffel tower in Paris. That was too deep for Fritz, so the Australian answered it himself. “Don’t you know, Fritz? Well, we have no blankets, you know.” Still the sentry did not get it. So the Australian carefully explained to me—so that Fritz could hear—that the Germans had no blankets and were using the flag to wrap their cold feet in, This started a fight, of course—the German idea of a fight, that is. The sentry, being a very brave man for a German, blew his whistle very loudly, and sentries came from all directions. So wt beat it to the Australian’s bar- racks, and there I found the second American in the camp. He was a bar- ber named Stimson, from one of the Western states. He had heard I was LaF | ees SH y much attention until XN Most of Those Who Ran Away Were Brought Back. completed his period of detention, He claimed that the sixth time he had really got across the border and was arrested in a little town by the Dutch authorities and turned over to the Ger- mans. That is against the law in most countries, but he swore it was the truth. i am not so sure, myself. He got away for the seventh time while I was at Dulmen and was not returned: Ten days in the guardhouse is not such a light punishment after all, be- cause water three times a day is all the prisoner received during that time, but it is pretty mild compared to some of the things the Huns do. One morning I thought for sure I was going cafard. I was just fed up on the whole business and sick of do- ing nothing but suffer. So I strolled along, sticking my head into barracks doors, sometimes trying to have a talk, other times trying to pick a fight. It was all one to me: I just wanted some- thing to do, I found what I wanted, all right. I had quite a talk with a sentry in front of a barracks, It*must have lasted three-quarters of an hour. He did not know what I was calling him, and I did not know what he was call- ing me. I could have handled him all right, but another sentry came up on my blind side and grabbed me and the talk was over. They dragged me to the commander of the camp and he instructed them to give me a bath. So they took me to the bathhouse, where I was stripped and lashed. All the time they were whipping me I was thinking what a joke it was on me, because I had been looking for excitement and had got more than I wanted, so I laughed and the Huns thought I was crazy sure. I was dumped into a vat of hot Water and at the same time my clothes were given a boiling, which was good for them. Then I was forced into my wet clothes and marched back to the bar- racks, This bath and the stroll through the snow in wet clothes just about did for me. Nowadays, when I ait in a draft for @ second and catch cold, I wonder that I am still alive to catch it. Having gone through Dix- mude and the Dardanelles and the sinking of the Georgic and four Ger- man prison camps and a few other things—I shall probably trip over a hole in a church carpet and break my neck. That would be my luck. There were all the diseases you can think of in this camp, including black cholera and typhus and somebody was always dying. We had to make coffins from any wood we could find. So it was not long before we were using the dividing boards from our bunks, pieces of flooring and, in fact, the walls of the barracks. The officers were quar- tered in corrugated iron barracks, so they had to borrow wood from us for their coffins. We would make the box and put the body in it, give it as much service as we could, in the way of prayers and hymns, and put it away in a hole near the barracks, There was so much of it that a single death passed unnoticed. One morning the German sentries came to our barracks—they never came singly—and told us that an offi- cer was going to review the prisoners and ordered us to muster up, which we did. I was the last man out of the bar- racks and on account of my wounds I was slower than the rest. You understand Ihad had no medical treatment except crepe-paper ‘“ban- dages and water; my wounds had been opened by swimming from the Georgic to the Moewe and they had been put in terrible shape in the coal bunkers, On account of the poor food and lack of treatment they had not even started to heal. bandages that any of us had were what we would tear from our clothes and I have seen men pick up an old dirty ad just about caught up with us, and there as well es the Boston man in the Tag that someone else had had around hen we would go on. We did this everal times until they got on to us, nd we could not do it any more. Up the road a piece I fell again, and us time I did nat care what hap- ened, so I just sat there in the uiddle of the road until Fritz came up. astead of giving me the bayonet, he aade me take off my shoes—that is, e took them off of me with a knife hrough the strings—and I had to walk he rest of the way in my bare feet. t was about four miles altogether rom the station to the camp. When we got near the camp, all the oys came out of the barracks and ined up along the barbed wire, and elled us a welcome. We asked them ¢ they were downhearted, and they aid no, and we said we were not elth- x. We could hardly see them, but hey began yelling again when we got searer, and asked us, “Is there anyone here from Queenstown?” and then iull, and Portsmouth, and Dover, and Toronto and a lot of other places, Canadian service, but he had been too sick to look us up, and in fact did not care what happened, he was so miserable. He had been wounded sev- eral times, and died in a day or two, I never knew how he came to be in the Australian service. Those two and myself were the only Americans I knew of in this prison camp—whether in Canadian, Austra- lian or French service. The other two had been captured in uniform, so there was no chance of their being released. Dulmen was very near the Dutch border and as it was quite easy to get out of the camp attempts at escapé were frequent. Most of those who ran away were brought back, though. The Germans were s0 easy on those who tried to run away that I almost thought they were encournging them. One chap was doing his ten days in the guardhouse for the sixth time while ‘L was there—that is, he had just about his wound for a long time and bandage his own wounds with it. So it was all I could do to drag my- self along. The officer noticed that I was out of line and immediately asked my name eud nationality. When he heard “American” he could not say enough things about us and called me all the swine names he could think of, I was pretty thin at this time and getting thinner, so I figured I might just as well have it out bhefere I starved, Besides, I thought, he ought to know that we are not used to being bawled out by German swine in this country. So I told him so, And I said that he should not bawl Americans out, be- cause America was neutral. He then sald that as America supplied food and munitions to the allies she was no bet- ter than the rest. Then I said: “Do you remember the Deutschland? When she entered Bal- timore and New London she got all the | cargo she wanted, didn’t she?” "Fea Incidentally, the onty cloth | “Well, if you send over your mer- chant marine they will get the same.” For that answer he gave me ten days in the guardhouse. He ati not like to be reminded that their merchant ma- rine had to-dive under to keep away from the Limeys. ‘ I admit I was pretty flip to this of- ficer, but who would not be when a slick German swine officer bawled him out? It was while I was in the guardhouse that-Mr. Gerard, the American ambas- sador, visited the camp. He came to this camp about every six months, as a rule, Even in tte German prison camps the men had somehow got infor- mation about Mr. Gerard's efforts to improve the terrible surroundings in which the men lived. Some of the mea at Dulmen had been’ confined in vari- onus other camps and they told me that when Mr. Gerard visited these camps all that the men did for a week or so afterward was to talk about his visit and what he had said to them, We knew Mr. Gerard had got the Germans to make conditions better in some of the worst hell-holes In Germany and the men were always glad when he came around, They felt they had some- thing better to look forward to and some relief from the awful misery. Mr. Gerard was passing through the French barracks and a man I knew there told him there was an American there. The Germans did not want him to see me, but he put up an argument with the commanding officer and they finally said he could interview me.. 1 never was so glad to see @nyone as I was to see him. The picture Is still with me of him coming in the door. We talked for about an hour and a half, I guess, and then he got up to go and he sald I would hear from him in about three weeks. Just think what good news that was to me! They let me out of the guardhouse and I celebrated by doing all the dam- age to German sentries that I could do. The men in the camps went wild when they learned that Ambassador Gerard was there, for they said he was the only man in Germany they could tell their troubles to, The reason was that he was strong for the men, no matter what nationality, and put his heart into the work, I am one of those who cannot say enough good things about him. Like many others, if it had’not been for Mr. Gerard I would be kaput by now. A few days after this I was slow again as we were marching to the bread house and the guard at the door tripped me. When I, fell I hurt my wounds, which made me hot. Now I had decided, on thinking it over, that the best thing to do was to be good, since I was expecting to be released, and I thought It would be tough luck to be killed just before I was to be released. But I had been in the Amer- ican navy and any garby of the U.S. A. would have done what I did. It must be the training we get, for when a dirty trick is pulled off on us we get very nervous around the hands and are not always able to control them. So 1 went for the sentry and wal- loped him in the Jaw. Then I received his bayonet through the fleshy part of the forearm. Most bayonet wounds that we got were in the arm. But those arms were in front of our faces at the time. The sentries did not aim for our arms, you can bet on that. A wound of the kind I got would be noth- ing more than a white streak if prop- erly attended to, but I received abso- lutely no attention for it and it was a long time in healing. At that, I was lucky; another bayonet stroke just grazed my stomach, I had been at Dulmen for three weeks when we were transferred to Brandenburg, Havel, which is known as “the hell-hole of Germany” to the prisoners. It certainly is not too strong a name for it, either, On the way we changed trains at Osnabruck and from‘ the station plat- form I saw German soldiers open up with machine guns on the women and children who were rioting for food. CHAPTER XXII. “The Hell Hole of Germany.” On arriving at Brandenburg we were marched the three or four miles north- west to the camp. While we were be- ing marched through the streets a woman walked alongside of us for | quite a way, talking to the boys in English and asking them about the war, She said she did not belleve anything the German papers printed. She said she was an: Englishwoman from Liverpool and that at the out- break of the war not being able to get out of Germany, she and her chil- dren had been put in prison and that every day for over a week they had put her through the third degree; that | her children had been separated from |her and that she did not know where | they were. She walked along with us for several blocks until a sentry heard her say something not very complimentary to the Germans and chased her away. When we arrived at the camp we were put into the receiving barrecks and kept there six days. The condition of these barracks was not such that you could describe It. The floors were ac- tually nothing but filth. Very few of ! the bunks remained; the rest had been torn down—-for fuel, I suppose, The day we were transferred to the regular prison barracks four hundred Russians and Belgians were buried. Most of them had died from cholera, typhoid and inoculations. We heard from the prisoners there before us that the Germans had come through the camps with word that there was an epidemie of black typhus and cholera and that*the only thing for the men to do was to take the serum treatment to avoid catching these diseases. Most of the four lndred men had died from the theent tions, hey hid tien the Germans’ word, had been inoculated and had died within nine hours, Which shows how foolish it is to believe a German. None of us had any doubt but what the serum was poisonous, ‘barbed wire all around our barracks. They told us we had a case of black typhus among us. This was nothing more nor less than a bluff, for not one ,of us hac typhus, but they put up the (wire, nevertheless, and we were not ‘allowed to go ont. One day when I was loafing around our barracks door and not having any- | thing particularly important to do, I | packed a nice hard snowball and Iand- |ed it neatly behind the ear of a little | sentry not far away. When he looked | around he did not blow his whistle but began hunting for the thrower. This was strange in a German sentry and I | thought he must be pretty good stuff. | When he looked around, however, all |he saw was a man staggering around |as if he were drunk. The man was | the one who had done the throwing, all right, but the sentry could not be sure |} of it, for surely no man would stay out in the, open and invite accidents So I just kept staggering around, | and the sentry came up to me and | looked me over pretty hard. Then I | thought for the first time that things | might go hard on me, but I figured that if I quit the play acting it would | be all over. So I staggered right up to the sentry and looked at him drunk- | enly, expecting every moment to get one from the bayonet. | But he was so surprised that all he | could do was stare. So I stared back, pretending that I saw two of him, and otherwise acting foolish. Then I guess | he realized for the first time that the | chances of anybody being drunk in that camp were small—at least for the prisoners. He was rubbing his ear | all the time, but finatly the thought | seeped through the ivory and he began to laugh. I laughed, too, and the first thing you know he had me doing it again—that is, the imitation. One snewball was enough, I figured. I used to talk to him quite often after that. We had no particular | love for each other, but he was gamer | than the other sentries, and he did not | call me schweinhund every time he saw | me, so we got on very well together. | His name must have been Schwartz, I } guess, but it sounded like “Swatts” to | me, so Swatts he was, and I was | “Chink” to him, as everybody else | called me that, } One day he asked me if I could | speak French, and I said yes. Italian; yes. Russian; yes. No matter what | language he might have mentioned I | would have said yes, because I could | smell something in the wind, and I | Was curious. ‘Then ke told me that if | I went to the hospital and worked p there, I might get better meals and | would not-have to go so far for them, | and that my knowing all the languages I said I did would help me a great ways toward getting the job. | Evidently he had been told to get a man for the place, because he ap- , Pointed me to it then and there. He | Put me to work right away. We went ‘over to one of the barracks, where n case of sickness had been reported, | and found that the invalid was a big | Barbadoes negro named Jim, a fire- /man from the Voltaire. At one time | Jim must have weighed 250 pounds, but by.this time he was about two pounds lighter than a straw hat; but | still black and full of pep. Light as he was, I was no “white hope,” and it | was all I could do to carry him to the hospital. Swatts kept right along be- i hind me, and every time I would stop _to rest, he would poke me with a broom—the only broom I saw in Ger- , Many—and laugh and point to his ear. Then I thought it was a frame-up and that he was getting even with me, but I was in for it then, and the best I could do was to go through with it. But I was all in when we reached the hospital. thin as Jim had once been short and fat. This black boy and I made a great¢team, but I never knew what his name was. I always called him Kate, because night and day he was whistling the old song, “Kate, Kate, Meet Me at the Garden gute,” or words to that effect, I have waked up many a night and heard that whistle just about at the same place as when I had fallen asleep. It would not have been so bad if he had known all of it. I took Swatts’ broom and cleaned ap, and then asked where the coal or wood was. This got a great laugh. It was quite humorous to the men who had shivered there for weeks, maybe, but to me it was about as funny as a ery for help. I got wood though, be- fore I had been there long. There was a great big cupboard that looked more Uke a smal! honse, bullt against the wall of the hasnital | barracks In one corner of the room, and not far from the stove. Kate was the only patient able to be on his feet, | so I thought he would have to be my | chief cook and bottle washer for a| ‘while; and, besides, there was some- .thing about him that made him look ‘pretty valuable. I had not recognized his whistling yet, so Slim looked to be jthe right name for him. | “Slim, what's that big cupboard for?” | “How'd I know? Nuthin’ in it.” “Slim, that would make a fine box ‘for coal or wood, wouldn't it?” | “Um, Whar de coal an’ wood?” | “I'm going out and take observa- (Hons, Sum. Take the wheel while I’m gone, and keep your eye peeled for ‘U-boats.” » So I sneaked out the door and began looking around, If you look at the sketch I have made, it will not take you long to see that next to us was a vacated Russian barracks, And it did not take me much longer to see it, too, Back to the hospital and Slim, “Slim, what barracks are next to us?” ' “Russian burrucks, only dey ain't dere now. Been sick.” “And you mean to tell me you don’t know where to get wood?" “Sick men been in dem burrucks.” “Bick men here, aren't there? Let's go” _ nee Lipton pgp bee ERAS Ae} See See EE The second Gay that We-were I the) Phat aia the ta ‘regular camp the Germans strung | would watch from the hospital win- he wanted to see himall the more. jlike that. But still, who had done it? | The first thing I saw when | we got in the¢door was another negro, | also from Barbadoes, and as tall and ' ‘The black Boy | dows until he saw the const was clear, then we would slip into the barracks next door, and he would watch again. When there was no sentry near enough to hear us, crash! and eut would come a dividing board from the | bunks, we had an armful apiece, and had broken them up to the right lengths, all we needed was & lit- tle more watching, and then back te the hospital and the big cupboard. Later on, our men told me they used to watch the smoke that poured from the hospital chimney all the time and wonder where on earth we got the | Wood. | We got the same kind of food in the hospital that was served in the other barracks, and I would not have had any more than I used to, except that sometimes some of the twenty-six pa- tients could not eat their share, and then, of course, it was mine, One day, though, we all had extra rations. Two Russian doctors came to visit |us each day, and once they were fool- ish enough, or kind enough, to ask if we had received our rations—we had received, them earlier than usual and they were finished at the time. Of course, I said no, so they ordered the Russian in the kitchen to deliver twenty-elght rations to us, which was not quite three loaves of bread. We were that much ahead that day, but it | Would not work when I tried the trick ‘again, One day a German doctor came to the hospital barracks, He would not touch anything while he was there— not even open the door, All of the patients had little cards attached to their beds—charts of their condition. | When the German wanted to see these charts the Russian doctors had to hold them for him. | I was having a great time at the hospital, wrecking the barracks next ldoor each day for wood, along with Kate, and getting a little more food sometimes, and was always nice and warm, I thought myself quite a pet. Compared to what I had been up against, it seemed like real com/ort. But the more food I got, the more I wanted. And it was food that brought me down, after all, | Across from us was a barracks in which there were English officers, and somehow it seemed to me that they must have had a drag. Every once in a while I saw what looked like vege- tables and bags of something that was a dead ringer for brown flour. So I told Slim, or Kate, as I was calling him by then, and with him on guard, I sneaked out, After two or three false starts, I got over our barbed wire and their barbed wire, and in through a window, There I saw carrots! And graham ;@our! | 1 took all I could carry, to divide up with Kate, and then started eating, so as not to waste anything. It was vertainly some feast—the only thing besides. mud -bréad and barley coffee and “shadow” soup that I had to eat in Germany. ‘Then I started back to the hospital, I got over their barbed wire all right, and Kate gave me the go-ahead for our entanglements, but just as I was going over them a sentry nabbed me, At first I thought Kate had turned traitor, because we had had a little argument a short time be- fore, But later on I figured that he would not have done a trick like that, and besides, he knew I was bringing him something to eat. So the sentry must have sneaked up without Kate seeing him. Who got the carrots and gra- ham flour that I was carrying I do not know. The sentries booted me all the way back to my old barracks, CHAPTER XxXill. Despair—and Freedom. While I was working at the hos- pital conditions at my old barracks had been getting worse and worse. Very few of the men were absolutely right in the head, I guess, and almost all had given up hope of ever getting out alive. Though they put up a good front to the Huns, they really did not care a great deal what happened to them. The only thing to think about ‘was the minute they were living in. The day I came back two English- men, who had suddenly gone mad, commenced to fight each other. It was | the most terrible fight I have ever seen. It was some time before the rest of us could make them anit. he- cause at first we did not know they | Were crazy. When we had them down, | however, they were scratched and bit- | ten and pounded from head to foot. | Both of them bled from the nose ali | that night, and toward morning one of them became sane for a few min- utes and then died. The other was | taken away by the Germans, still crazy, Another time an Australian came into our barracks and yery seriously | told us that he had a drag with the German officers and that he had been to dinner with them, and had had tur- key, ‘potatoes, coffee, butter, eggs, | sugar in his coffee, and all the luxuries you could think of. We just sat and | Stared at him. It seemed impossible | that any of our own men would have the gall to torture us like that, and yet | We could not possibly believe that it | had really happened, Finally, one fellow could not stand it any longer. | He was nothing but skin and bones, but he grabbed a dividing board and there were just two wallops: the board hit the Australian’s head and the head hit the floor. Then half a dozen more pounced onto him and gave him a reat Mcking. When he came to he had forgotten all about the wonderful dinner he did not have. tors proved to the Germans that there was no black typhus in our barracks and we were allowed the freedom of the camp except that we could not visit the Russian barracks. That was ;no hardship to me nor to the rest of us, except one chap from the Cambrian pire ealvedicorcthcgugheen epegrend the Russians that Not long after this the Russian doc.’ Knd, of coutse, when lt was verboten, A day or two after the order I was | standing outside the barracks door when I saw this fellow come out with a dividing board in his hand. I thought he was going to smash somebody with it, so I stood by. But he stooped over and jammed one end of the board against the threshold of the door, scratched the ground with the farthér end of the board and measured again. He kept this up, length By length, in the direction of the Russian barracks. The sentry in the yard stopped and stared at him, but the fellow kept | Fight on, paying no attention to any- |body. Pretty soon he was right by the sentry's feet and I thought any minute thé sentry would give him the butt, but he just stared a while and let him pass, That iad measured the whole distance to the Russian barracks, went inside, stayed a while and calmly strolled back with the board under his arm, When he reached our barracks again he told us he had found a vino © mine. What he had found was some- thing not so unusual—ao boneheaded ‘German, ‘There was n lot of bamboo near the Russian barracks and the Russians ‘made baskets out of it and turned them in to the Germans. For this they got all thé good jobs in the kitchen jand had a fine chance to get more to ‘eat. But they were treated like dogs— \that is, all except the few Cossacks that were in the bunch, The Huns knew that a Cossack never forgets and will get revenge for the slightest mis- treatment, even if it means his death. I have seen sentries turn aside from the beat they were walking and get out of the way when they saw a Cossack coming. There were very few Coss- acks there, however. I do not think they let themselves get captured very often. We had roll call every morning, of course, and were always mustered in front of our barracks, the middle of the Iine being right at the barracks door. Sometimes when the cold got too much for them, the men nearest the door would duck into the bar- racks. As they left the ranks the other men would close up and this kept the line even, with the center still opposite the barracks door. Finally almost all of the men would be in the barracks and by the time the roll was over not one remained outside. This seemed to peeve the German officers a great deal, but they did not punish us for it until we had been doing it for some time. For several days I had noticed that Someone else answered for two men who had disappeared; at least I had not seen them for some time. I did not think much about it, or ask any questions, and I did not hear anyone else talk about it, but I was pretty sure the two men, a Russian and a Britisher, had escaped. But they were marked present at roll call and all accounted for. Everything went along very well until one day when the name “Fontaine” got by without being an- swered. Fontaine was a French fire- man from the Cambrian Range and that was the first time he had not been present. We saw what was coming and we began to get pretty sore at Fontaine for not telling us, so we could answer for him and keep the escape covered, The minute they found our count one short they blew the whistles and a squad of sentries came up as an extra guard. They counted us again, but by sneaking back of the line and closing up again we made the count all right except for one man—Fon- taine. We would have tried to cover | up for him, excent that they had al- ready discovered his absence. Now, we thought, they will nab Fontaine but will not discover the escape of the others, But evidently they suspected some- thing, for soon they brought over a petty officer from H. M. S. Nomad, who had not been’ with us before, and forced him to call the roll from the mustering papers, while they watched the men as they answered. Then they ‘iscoyered that two more besides Fon- talne were missing and began to search for them. G@ONILNOO Gd OL a The Fourth Liberty-Loan Commit- tee has about wound up its work for this campaign. The coming week is left for the cleaning up of unfinished busines# and to give those who have not had a chance to purchase during the drive, an opportunity to sub- scribe. The Casper National Bank will be paee to take subscriptions at any time during the day or evening the coming week. 10-14-1t * * ° CARD OF THANKS We wish to extend our most sin- |cere thanks tp our friends for the |kindness and sympathy extended to jus during our recent bereavement in \the death of our son, Orin, who lost | his life on the battlefields of France. | MR, AND MRS. 0. E, SNYDER | AND FAMILY, 10-14-1t Salt Creek, Wyo. * + * Money to loan on everything. The Security Loan Company, Room 4, Kimball Bldg. 10-1-tf The women thruout Canada are preparing to take a prominent part n the approaching Victory Loan campaign. i Grand Union Tea Co, We are again represented in Casper by Frank G. Pierce and when in need of good Tea, Cof- fee, Spices, Toilet Articles, etc., phone 312-J. (CL